-

Architects: ALH Taller de Arquitectura

- Area: 370 m²

- Year: 2021

If you want to make the best of your experience on our site, sign-up.

If you want to make the best of your experience on our site, sign-up.

Recent extreme weather events and the acceleration of climate change, paired with decarbonization efforts that are not on track, make climate-related disruption unavoidable for urban environments, raising the issue of climate-risk adaptation. Moving past what can be done to prevent climate change, there is a strong imperative to develop strategies to prepare urban environments to cope with inevitable challenges such as sea-level rise, floods, water scarcity or extreme heat. The following discusses how cities can build resilience and adapt to undergoing and expected future climate threats.

Social Urbanism: Reframing Spatial Design – Discourses from Latin America, a new book by Maria Bellalta, ASLA, dean of the School of Landscape Architecture at the Boston Architectural College, is a welcome addition to the growing number of publications on the social justice-oriented form of urbanism, architecture, and public space emanating from Medellín and Colombia. The achievements of social urbanism have rightfully become synonymous with Medellín in the world of landscape architecture, urban planning and design, and architecture.

While developing a master plan for Medellin's urban lighting system, EPM, Medellin's public utility company, analyzed the Colombian city's infrastructure and nocturnal lighting system by superimposing a map of the system over a map of the city. What they found was an urban landscape blotted by "islands" of darkness.

Much to the surprise of the utilities company, the dark spots were actually 144 water tanks that were initially built on the city's outskirts; however, thanks to the progressive expansion of Medellin's city limits, the tanks now found themselves completely surrounded by the informal settlements of the Aburra Valley. Even worse, they had become focal points for violence and insecurity in neighborhoods devoid of public spaces and basic infrastructure.

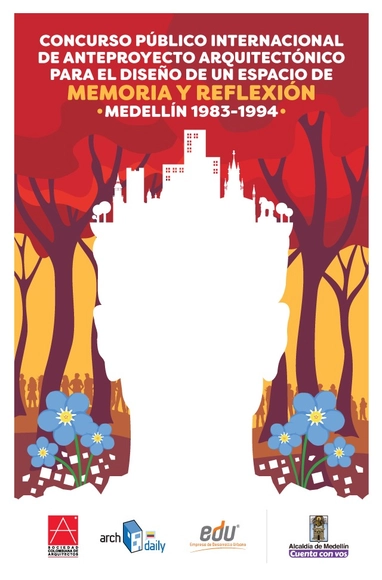

With the help of Empresa de Desarrollo Urbano/Urban Development Company (EDU) and La Sociedad Colombiana de Arquitectos/the Colombian Architect's Society (SCA), Medellín has launched an international competition to design a space to remember and reflect on the period between 1983 and 1994.

These years were some of the most violent in the Colombian city's history. In January 1988, a car bomb with 80 kilos of dynamite exploded in front of the Monaco Building, the former home of drug lord Pablo Escobar in El Poblado neighborhood. This was the first of a series of attacks between rival drug cartels in Medellin.

After a series of failed attempts, the Monaco building in Medellín will finally be demolished at the beginning of 2019, according to the Colombian newspaper El Tiempo.

The Monaco building, which was converted into a municipal asset this year, was the residence of the late drug trafficker Pablo Escobar in the El Poblado neighborhood of Medellín. In January of 1988, a car bomb with 80 kilograms of dynamite exploded in front of the building giving rise to a series of attacks between the drug cartels in Medellín.

Mercer released their annual list of the Most Livable Cities in the World last month. The list ranks 231 cities based on factors such as crime rates, sanitation, education and health standards, with Vienna at #1 and Baghdad at #231. There’s always some furor over the results, as there ought to be when a city we love does not make the top 20, or when we see a city rank highly but remember that one time we visited and couldn’t wait to leave.

To be clear, Mercer is a global HR consultancy, and their rankings are meant to serve the multinational corporations that are their clients. The list helps with relocation packages and remuneration for their employees. But a company’s first choice on where to send their workers is not always the same place you’d choose to send yourself to.

And these rankings, calculated as they are, also vary depending on who’s calculating. Monocle publishes their own list, as does The Economist, so the editors at ArchDaily decided to throw our hat in as well. Here we discuss what we think makes cities livable, and what we’d hope to see more of in the future.

Jaime Lerner defines urban acupuncture as a series of small-scale, highly focused interventions that have the capacity to regenerate or to begin a regeneration process in dead or damaged spaces and their surroundings.

Rather than urban acupuncture, the intervention that took place in the rugged geography of Medellin’s Comuna 13 was like an open-heart surgery, a large-scale action aimed at bringing about physical and social change of what was once one of the most dangerous neighbourhoods in the world’s most dangerous city.

The bilingual guides take us through the neighbourhood, showing us the escalators that gave the intervention worldwide fame. At the same time, in one of the many refurbished squares, a CNN team records interviews with locals and foreigners who visit by the hundreds what was, until recently, an unlikely tourist destination. A drone flies over the scene, we do not know if it is operated by the omnipresent police, CNN or tourists.

.jpg?1503039492)

.jpg?1479223605&format=webp&width=640&height=580)

In the Colombian city of Medellin, a new headquarters is being constructed for the Empresa de Desarrollo Urbano (Urban Development Company), combining optimal thermal performance with local urban regeneration. The new EDU headquarters is the result of a three-part collaboration between the public company, the private sector, and Professor Salmaan Craig from the Harvard Graduate School of Design who has family roots in the Colombian capital.

Constructed on the site of the former EDU headquarters on San Antonio Park, the scheme aims to act as a benchmark for sustainable public buildings in Medellin, embracing the mantra of “building that breath."

As a specialist in materials, thermal design, and building physics, Professor Craig (EngD) voluntarily offered his service to the scheme’s realization. Below, he explains the thermodynamic challenges behind the building’s conception.