Choreographies, an installation at the 4th Lisbon Architecture Triennale by Pedro Alonso and Hugo Palmarola, presents the construction of building sites as cultural and political archetypes. By critically contesting comic films and animated cartoons released in the United States and the Soviet Union between 1921 and 1980, it presents construction sites as places in which ideology and imagination were combined through the choreographic movements of hanging steel-beams in the US, and flying concrete-panels in the USSR. These building components symbolize the construction of the modern world, the technological optimism of industrialization, the relevance of the building process over the completed building, and the standing of workers—welders, riveters and crane operators—against the vanishing figure of the architect.

These Choreographies are presented by a simultaneous projection of two looping films, screening selected fragments from movies and animated cartoons in order to stress both the symmetries and differences between the USA and the USSR in, for example, opposing beams to panels, riveters to welders, and skyscrapers to housing blocks. This selection highlights the mise-en-scène of buildings sites in film, including visual gags on Taylorism, parodying the industrial production of steel beams and concrete panels.

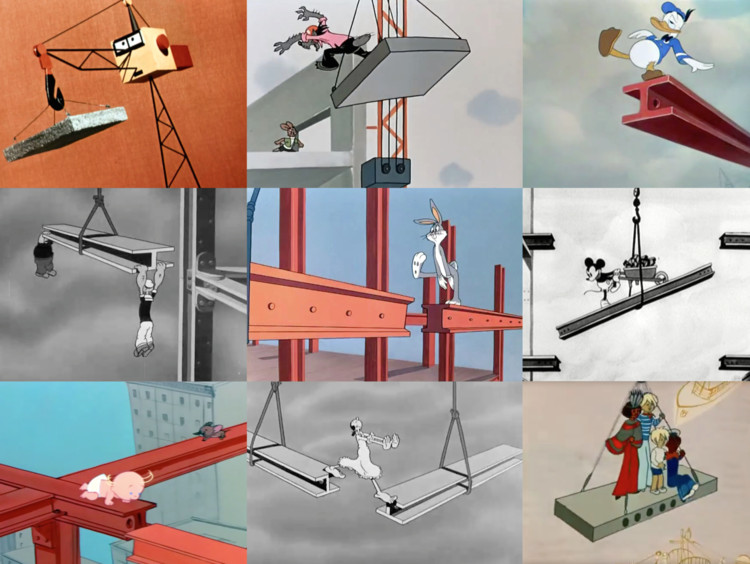

In America, Harold Lloyd’s silent comedy Never Weaken (1921) was the first comic film presenting a steel beam that casually comes through the window of a building. As it does, Lloyd performs all sorts of acrobatic movements in the context of the skyscraper construction boom and the economic prosperity of the 1920s. This film later became a fundamental reference to the work of various animation studios including Looney Tunes, Walt Disney and Fleischer, each having their own well-known characters to conduct feats similar to Lloyd’s. This is the case of Bosko, Mickey Mouse, Popeye, Olive Oyl, Porky, Mr. Magoo, Bugs Bunny, Tom and Jerry, Daffy Duck, and Droopy, in short animations such as Hold Anything (1930), Building a Building (1933), A Dream Walking (1934), Bridge Ahoy (1936), Porky's Building (1937), The Riveter (1940), Rhapsody in Rivets (1941), Nix on Hypnotricks (1941), Construction Mayhem (1949), Homeless Hare (1950), Child Sockology (1953), Tot Watchers (1958), Cat Feud (1958), Pent House Mouse (1960), Base on Bawls (1960), Bad Day at Cat Rock (1965), Skyscraper Caper (1968), Droopy's Restless Night (1980), and Droopy's Good Luck Charm (1980).

In the Soviet Union, it was Cheryomushki (1963)—a film based on an operetta by Dimitri Shostakovich—which praised the newly established policy towards the use of large-concrete panel construction, a building technology promoted in the 1950s by Nikita Khrushchev. This movie had a climax in the frenetic dance of a couple on top of a panel while being transported through the air. Cheryomushki and the later comedies Operation Y and Shurik’s Other Adventures (Operatsiya Y i drugie priklyucheniya Shurika, 1965), were followed by many other short animations that took the theme of the flying panel, such as The Story of a Crime (Istoriya odnogo prestupleniya) (1962), How the House Was Built to the Kitten (Kak kotenku postroili dom) (1963), Granny's Umbrella (Babushkin zontik) (1969), At the Port (V portu) (1975), the opening animated cartoon of The Irony of Fate, or Enjoy Your Bath! (Ironiya sudby, ili S lyogkim parom!) (1975), and I'll get you! (Nú,! pogoduí!) (1976).

In these animations, steel-beams and reinforced-concrete panels are denoted as weightless elements that reach the sky thanks to technology, construction and architecture. In the United States these cartoons gave value to skyscrapers and their role in the development of capitalism. In Soviet Russia these films took the choreographic movements of panels carried by cranes, symbolizing egalitarianism and a raw aesthetic that took up some principles of constructivism, intended to replace the Socialist Realism of Joseph Stalin. In both, beams and panels were key elements of the plot of the films, reflecting the two most representative structural paradigms of the twentieth century. Because its primary function was to amuse, the films were successful in presenting in a simple way construction sites as belonging to the daily life of cities, but without the burdens assigned to them by the histories and theories of modern architecture and urbanism.

In both the United States and the Soviet Union beams and panels never stop moving. Such endless motion is not accidental but central to the comic plot, as well as the jokes that are all too similar. The only substantial change is the preferred building component chosen by capitalist America and communist Russia: fearless acrobatics high up in the structures, jumping or dancing from beam to beam and from panel to panel, characters chasing each other, somnambulism, unconscious walks, or sudden vertigo that may be taken as tokens of utter the confidence on the technologies and their sustaining ideologies, subtlety admitting they are at the same time teasing danger. As long as they were addressing general public and children, the building sites of dancing beams and panels were battlefields in the construction of a certain consciousness displaced towards politics, ideology and education. Beams and panels were not only sustaining structural loads, but also a whole range of cultural weights.

Outside cinema, however, one of the most famous images on a steel-beam is Lunch atop a Skyscraper (1932), in which eleven workers are having lunch on a large metal beam on the 69th floor, during construction of the RCA Building in Rockefeller Centre in New York. The image, although staged, reflects the job insecurity caused by the Great Depression when risky tasks were accepted without proper safety standards. Coincidentally, within the same decade, and in contrast to that image, animated cartoons started to portray an opposite imagery. In A Dream Walking (1934) Olive Oyl sleepwalks on the moving beams of a building site. Wearing only a nightshirt that was transparent to the moonlight, she puts her bare feet on beams as they appeared on her way, making a remarkable choreography. Virtually every of the American cartoons of this series seem to insist that the beam is a safe way to walk in, even if their starring characters are, for different reasons, absolutely unconscious. These characters, in Giorgio Agamben’s words, are the ones “who can walk on thin air as long as they don't notice it; once they realize, once they experience this, they are bound to fall” [in: Infancy and History: The Destruction of Experience]. Quite like the irrational walking choreography of Olive Oyl, we shall never fall because that was the time of total confidence in the structural paradigms of beams and panels, elements forming solid imaginary structures that created reliable ways for Americans and Soviets to face the dangers of industrialization and progress, even in state of unconsciousness.

Pedro Ignacio Alonso and Hugo Palmarola, Choreographies. Simultaneous animated loops, 2:56 min. Compiled, edited and produced by Paulina Bitran. Credits: Pedro Ignacio Alonso and Hugo Palmarola, 2016. Music: Akai 47 by Nortec Collective presents: Bostich & Fussible (Courtesy of Nacional Records and Canciones Nacionales). Work sponsored by DIRAC of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Chile, and the Dirección de Artes y Cultura, Vicerrectoría de Investigación de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

Título

4.ª Trienal de Arquitectura de Lisboa: Choreographies - Pedro Alonso y Hugo PalmarolaTipo

ExhibiciónSitio Web

Organizadores

Desde

October 05, 2016 12:00 AMHasta

December 11, 2016 12:00 AMLugar

Fundación Calouste GulbenkianDirección