In the late 1970s, the Government of India launched an initiative to build in every state capital an institution to celebrate the cultural and creative output of the nation. Although the scheme was largely unsuccessful, one shining example remains: Bharat Bhavan (‘India House’), located in Bhopal.

Designed by Indian architectural luminary Charles Correa, this multi-arts center first opened its doors in 1982. More than thirty years later, it continues to house a variety of cultural facilities and play host to multitude of arts events. The design of the complex is a product of Correa’s mission to establish a modern architectural style specific to India and distinct from European Modernism. Drawing on the plentiful source material provided by the rich architectural heritage of his home country, at Bharat Bhavan Correa produced a building for the modern era which manages to also remain firmly rooted in the vernacular traditions of India’s past.

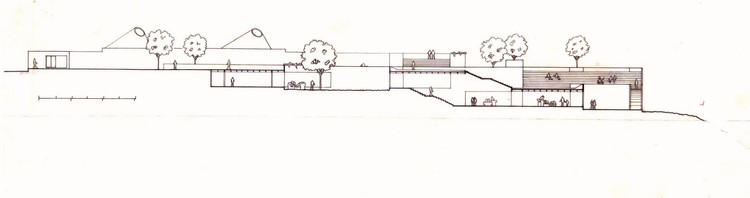

Built into a hillside which slopes down toward a lake, a series of terraces and courtyards comprise the complex. Upon entering, the visitor has the choice of following the path of terraces cascading down to the lake, or descending to the three courtyards which provide access to the majority of the cultural facilities. These include contemporary art galleries, a museum of tribal art, an auditorium, a library of Indian poetry, a print shop, and a studio for an artist-in-residence. From the courtyards, wide glass-paneled openings to the buildings ensure the arts program is both literally and figuratively accessible to all. At the bottom of the site sits an amphitheater, where open-air performances take place with the lake forming a natural backdrop.

The route through the terraces encourages movement down the site’s natural gradient, with the courtyards providing tranquil spaces for rest and relaxation. The dialogue between these two components creates an ebb and flow of energy around the complex, in what Correa described as a “Ritualistic Pathway”. The ritual of following a sacred pathway is, he claims, “a universal impulse, found in all cultures and religions.”[1] Correa emphasized the spirituality of his own pathways by drawing parallels with those found in religious architecture, including “the sun temples of Mexico” and the Hindu temples of Bali “with their ritualistic pathways up the hillside.”[2]

Correa also noted secular examples of the Ritualistic Pathway, such as the palace city of Fatehpur Sikri and Le Corbusier’s promenade architecturale, though he claimed the latter was merely “a ‘secular’ phrase to express what is in reality a deep and sacred instinct.”[3] At Bharat Bhavan, the flights of stairs between the terraces reference traditional Indian architecture while implying the sanctity of the pathway. The stairs are reminiscent of ghats; steps found in Indian cities which lead down to a body of holy water, just as Correa’s steps guide the pedestrian to the lakeside. Indeed, Correa cited the bathing ghats on the bank of the River Ganges at Varanasi as a stylistic influence.[4] At Bharat Bhavan the steps guide the pedestrian to the lakeside; the religious connotations emphasizing the sacred nature of this pathway.

European Modernism, and in particular that of Le Corbusier, had heavily influenced modern architecture in India for much of the 20th century. Correa was somewhat wary of this trend, and criticized Le Corbusier’s Palace of the Assembly at Chandigarh for being poorly ventilated, insufficiently lit, and wholly unsuitable for India’s hot and humid climate.[5] Correa’s architecture, conversely, is shaped by its environment, with climate control a primary concern in his design process. Indeed, this was often a necessity, as much of his early work consisted of projects for squatter housing, where inhabitants did not have the means to pay for air-conditioning and were forced to rely on the building itself to regulate temperature.

Rather than importing the “sealed boxes” of European architecture, necessitated by the colder Western climate, instead Correa created “open-to-sky spaces.”[6] He observed that “in a warm climate, the best place to be in the late evenings and in the early mornings is outdoors, under the open sky.”[7] The sunken courtyards at Bharat Bhavan provide shade from the scorching midday sun, while the raised terraces offer refreshing air and space at cooler times of day. This climate-control solution was lifted directly from India’s architectural history, inspired by the courtyards and terraces of the Red Fort at Agra.[8]

The sky held a spiritual power and mythical significance for Correa, who described it as “the abode of the gods” and “the source of light – which is the most primordial of stimuli acting on our senses.”[9] He aimed to harness the power of the sky to create a metaphysical experience through architecture, proclaiming that “there is nothing so profoundly moving as stepping out into an open-to-sky space and feeling the great arch of the sky above.”[10]

At Bharat Bhavan, the intention is that those emerging from the galleries to the courtyards undergo a similarly dramatic spatial experience. The sky is even incorporated into the interior spaces of the site, with concrete ‘shells’ atop the structure allowing light and air to pour in through their circular openings. From the exterior, these shells seem to reinterpret another feature of India’s architectural vocabulary: the decorative chattris (‘umbrellas’) which originally sat atop Rajasthani palaces.

The outdoor spaces at Bharat Bhavan are physical manifestations of the concept of “Empty Space,” a recurring theme both in India’s visual culture and, in particular, its philosophy.[11] Away from the activity within the buildings, the courtyards provide a contemplative void, enhanced by the placing of sculptures in their center. These act a meditative focal point for the viewer, much like the solitary tree often found in the center of Japanese courtyards. Correa’s characteristic use of the void as an architectural tool has been widely described as ‘non-building’. He marveled at the expressive potency of nothingness, reflecting that it is “strange indeed that since the beginning of time, Man has always used the most inert of materials, like brick and stone, steel and concrete, to express the invisibilia that so passionately move him.”[12]

The long-term success of Bharat Bhavan is largely due to its enduring popularity with local residents. The courtyards create communal public space, with the steps around their peripheries providing articulated seating for residents to meet and socialize. The terraces have proven popular with families, who spend their evenings promenading down to the water’s edge and enjoying the cultural offerings of the complex.[13] In creating a building well-suited to the needs of contemporary society while making use of familiar architectural motifs, Correa manages to reconcile modernity with tradition; a significant step towards his goal of establishing a distinctly Indian Modernism.

References

[1] Correa, Charles. “Snail Trail”. In Irena Murray. Charles Correa: India’s Greatest Architect. RIBA: London, 2013. P.6

[2] Correa, Charles. “A Place in the Sun”. In A Place in the Shade: The New Landscape and Other Essays. Hatje Cantz: Ostfildern, 2012. p.19

[3] Ibid. Correa. p.7

[4] Correa, Charles. “Blessings of the Sky”. In Kenneth Frampton. Charles Correa. Thames and Hudson: London, 1996. p.25

[5] Correa, Charles. “The Assembly at Chandigarh”. In A Place in the Shade: The New Landscape and Other Essays. Hatje Cantz: Ostfildern, 2012. p.13

[6] Ibid. Correa. “Blessings of the Sky”. p.25

[7] Ibid. p.18

[8] Ibid. Correa. “Snail Trail”. p.6

[9] Ibid. Correa. “Blessings of the Sky”. p.28

[10] Correa, Charles. Housing and Urbanisation. Thames and Hudson: London, 2000. p.7

[11] Murray, Irena. Charles Correa: India’s Greatest Architect. RIBA: London, 2013. p.22

[12] Ibid. Correa. “Blessings of the Sky”. p.27

[13] Frampton, Kenneth. Charles Correa. Thames and Hudson: London, 1996. p.45

-

Architects: Charles Correa

- Area: 120000 ft²

- Year: 1982

-

Photographs:Charles Correa Foundation, Patrick Barry