Just off the highway that leads to the town of Columbus, Indiana, the most slender of spires shoots upward from the tree line. With only a small gold cross at the top suggesting its purpose, the spire seems to belong to another world, an expressive gesture reaching into the sky that extends far beyond its visible tip. As visitors approach, the base of the spire fans out and merges with the ground, subsuming it and metaphysically bridging the distance between the heavens and the Earth. This is the famous North Christian Church, Eero Saarinen’s stunning discourse on God, nature and architecture.

Even in Columbus, a place known for its remarkable assemblage of modern architecture, this church is special. When Saarinen was selected to design the building in February, 1959, he was already a favorite adopted son of the town, having previously designed the private residence of the town’s patron, J. Irwin Miller, and the nearby Irwin Union Bank to great success. Miller, the wealthy owner of a local engine factory, was an avid lover of modern architecture and took it upon himself to bring many of the world’s great talents to work in Columbus, including I.M. Pei, Robert Venturi, Eliel Saarinen, Richard Meier, and Cesar Pelli. Miller personally served on the building committee for the new church, and it was said that Saarinen was selected for the job without even having to show a single slide of his work. [1] When the architect tragically passed away before the building’s completion, the effort to build the church became a tribute to his memory and his many contributions to the town.

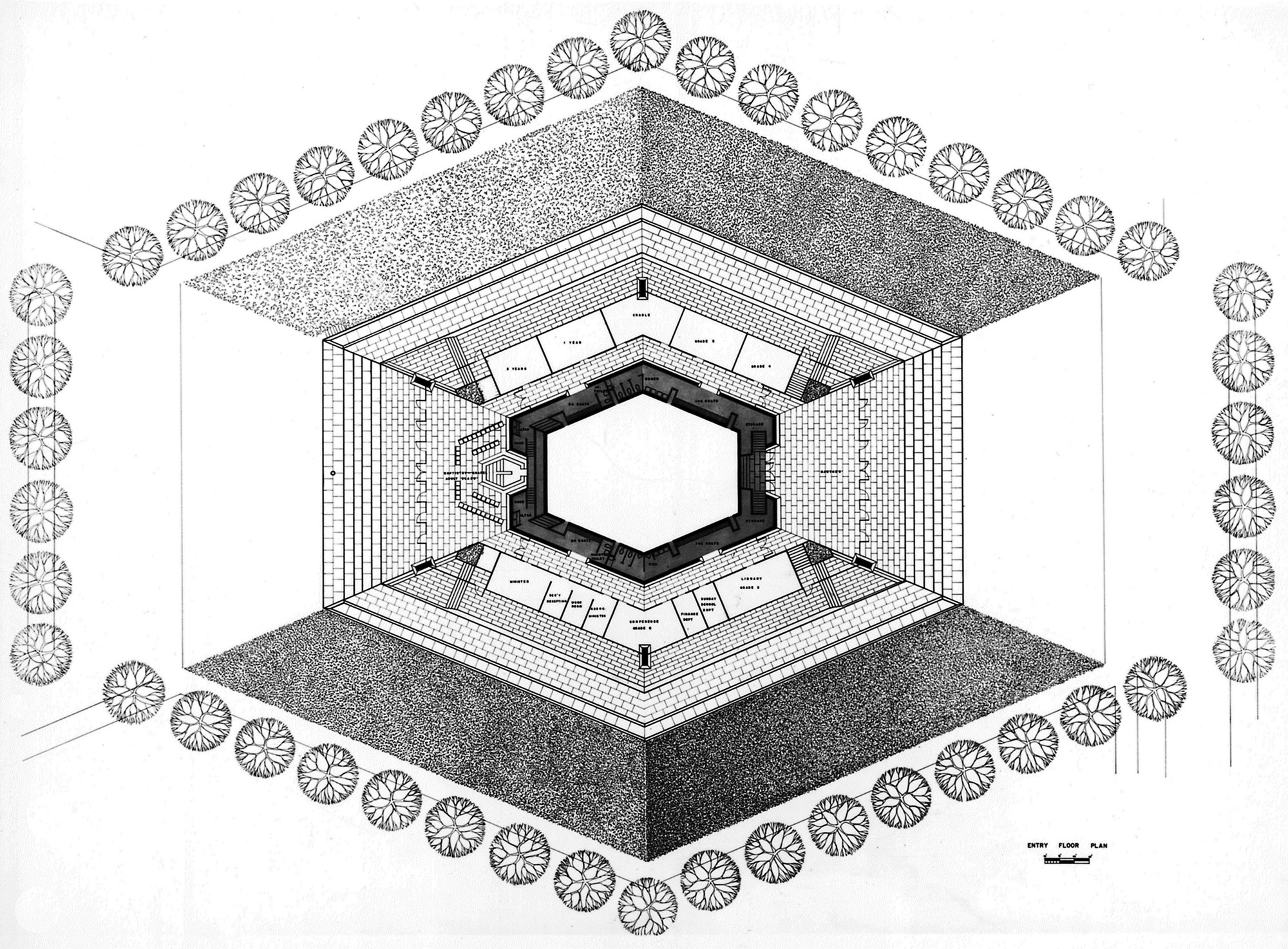

As is often the case with Saarinen’s buildings, the geometry of the church is elegant in its simplicity and ingenious in its structural arrangement. In plan, the church is a simple hexagon, elongated slightly along the East-West axis with entrances on the shorter sides. From each corner of the hexagon, massive piers support the structural ribs of the roof that converge at the top of the roof and angle upward into a spire. The height of the building rises to a soaring 192 feet, just shy of the 200-foot mark that would have required the unwilling architect to place an airplane beacon atop the gold cross.

Inside, the sculpted lines of a cast-in-place concrete ceiling beautifully mirror the angular geometries of the plan and cast a heavy presence over the worshipping space below. Eerie natural lighting is provided by a lone oculus over the central altar and is supplemented by a dance of dim artificial lights over the smooth concrete ceiling. A dark, natural material pallete consisting of gray slate floors and mahogany pews completes the cave-like ambiance.

The church’s famous design was conceived as a response to changes that Saarinen noted in contemporary religious construction. In his view, modern sanctuaries had become afterthoughts to massive complexes of secondary spaces in church buildings, which invariably included gathering spaces, classrooms, and even recreational lounges. While an expanded religious presence was not inherently a bad thing for Saarinen, the shift of focus away from the act of worship seemed to de-center God from religion. His objective was therefore to design a building that could meet contemporary needs without losing focus of the church’s original function as a place for worshipping and coming closer to God.

Programmatically, Saarinen communicates these priorities first by simply discriminating between primary and secondary church functions and placing them on separate floors. The aboveground level is devoted to the large central sanctuary and the ambulatory that surrounds it. The remaining spaces required by the clients – the bathrooms, kitchen, and fellowship hall – are buried into the ground, literally and symbolically placed beneath the worship space.

The layout of the sanctuary furthers elevates the role of worship with an unusual, centrally located altar. Seating for the congregation emanates upward and outward from it in ripple-like rings, directing the parishioners’ attention toward the center and demanding their active participation in the service. A dramatic entry sequence that requires visitors to “climb into” the sanctuary by ascending upward with the landscape before going back down works to the same effect, turning the altar into an object of destination and arrival. [2] The simplicity of the single gesture of the church – a sweeping move from the ground into the sky – is a further commentary on the simple, singular focus of the ideal church.

From the earthy materials to the dramatic formal geometries, the architecture strives to create a religious atmosphere that is intimate, unique, and transcendent. Stark experiential changes in the journey from the exterior to the building’s interior reflect a deliberate transition intended to magnify the worshipper’s spiritual journey.

Only one month after submitting the final version of his design, Saarinen passed away suddenly and unexpectedly at the age of 51, cutting tragically short the career of one of the twentieth century’s most accomplished and still-promising architects. This church, of which he was so proud, was the last building he would ever design. Its otherworldly form has been copied many times since its completion, and it has become perhaps the most recognizable icon of Columbus. In 2000, only thirty-six years after its completion, it was designated a National Historic Landmark as a testament to its value to the town and to postwar American architecture.

[1] Merkel, Jayne. Eero Saarinen. London: Phaidon Press, 2005

[2] Saarinen, Eero and Aline Saarinen, ed. Eero Saarinen on His Work. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968.

-

Architects: Eero Saarinen

- Year: 1964

-

Photographs:Flickr user Danube66, Flickr user noktulo, Hassan Bagheri