2022 has been the year of AI image generators. Over the past few years, these machine learning systems have been tweaked and refined, undergoing multiple iterations to find their present popularity with the everyday internet user. These image generators—DALL-E and Midjourney arguably the most prominent—generate imagery from a variety of text prompts, for instance allowing people to create conceptual renditions of architectures of the future, present, and past. But as we exist in a digital landscape filled with human biases—navigating these image generators requires careful reflection.

Midjourney is a particularly interesting Artificial Intelligence tool, proving popular amongst artists and designers alike for its painting-like, imaginative images created from sometimes very minimal text prompts. But the results fed back using this tool also raise complicated questions surrounding image-making and design, questions brought to the forefront when using prompts like “African architecture” to produce images.

The term “African architecture” is in itself quite contentious—a continent of nations with distinct architectural modes of practice. Debates have previously abounded, and continue to take place, on the usefulness of certain geographical labels such as “sub-Saharan Africa”, and a multitude of conversations have been had on the harmful framing of the African continent as a singular country.

At the same time, the history of European colonialism on the continent has led to blocks of African nations sharing similar colonial and post-colonial infrastructures, sometimes necessitating the grouping of select African countries under a common categorization—such as the parallels found in colonial and independence-era Tropical Modernist structures in Ghana and Nigeria.

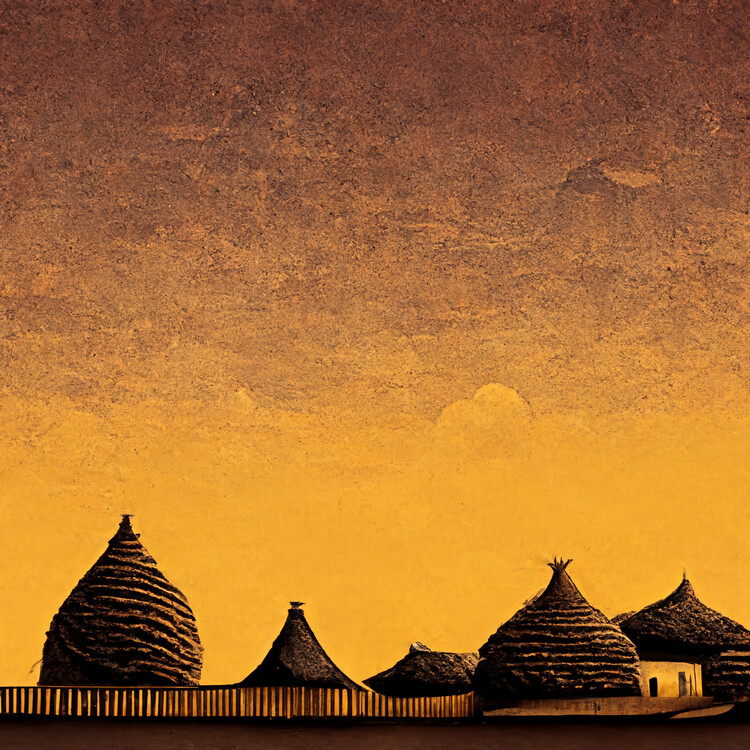

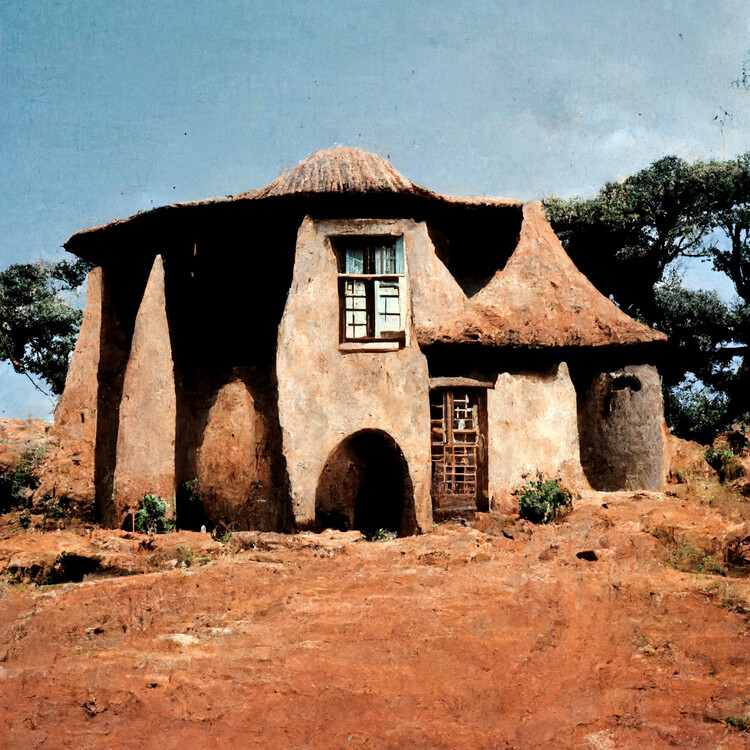

On Midjourney, typing in the prompt “African architecture” has produced images of hut-like forms, topped by what looks like thatched roofs in a seemingly rural environment. The prompt “vernacular architecture in Africa” has produced images similar in nature, hut-like buildings with acacia trees in the background, and reddish-brown earth in the foreground. These forms are evidently commonplace across the continent—from the examples of Sukuma traditional architecture found in the Bujora Museum in the Tanzanian city of Mwanza to the rondavel huts found across Southern Africa. But despite these general prompts—there is a plain lack of diversity in the type of images created, neglecting forms such as the flat-roofed earthen buildings found in the Moroccan province of Ouarzazate, or even the extremely diverse urban architecture in Africa’s metropolises.

The generation of images of these types with those specific prompts reflects wider issues of how the African continent is viewed online—from the lack of access to content in many African languages to the persisting nature of reductionist narratives about the African continent across the web. Nuance in the “African architecture” productions by the image generator model is not readily visually apparent. For comparison’s sake, the prompt “European Architecture” has depicted what appears to be grand streetscapes not out of place in Brussels or Paris, but again, there is a lack of variety, as the model eschews more Modernist buildings and feeds back architectural forms that would fit the mold of neoclassicism.

AI generative art algorithms usually function by drawing on large image banks of a particular subject in order to train their AI models. For Midjourney, public datasets are used to produce the outcomes generated by text prompts, and naturally, the prejudices present in publicly-available images and how they are classified will seep through to the art generated by models trained on these images.

The “African architecture” and “vernacular architecture in Africa” images composed by the AI most likely are the result of oversimplified captioning of images of African architecture online, not to mention how visual results of “African architecture” can still be very one-dimensional when one enters that text into an online search engine.

Of course, one has the option of entering more specific text prompts into the AI instead of general, encompassing labels like “African architecture” or “European architecture”. Entering the prompt “architecture of Nairobi in the 2050s” for example returns images of skyscraper-lined avenues in the Kenyan capital interspersed with the greenery of Uhuru Park—with hazy forms reminiscent of the Teleposta Towers and the Times Tower in the background. But using these more precise prompts still means that the imagery made from more wide-ranging prompts in the vein of “African Architecture” suffers from overgeneralized depictions—reinforcing a scenario that repeats the problematic foreshortening of the visual idea of African architecture.

Much has been said about what type of knowledge is dominant in machine learning and how many algorithms do not accurately represent the global context we live in. And as designers, artists, and everyday hobbyists—in the still-early days of competent AI image generators—continue exploring and testing creative concepts through programs, it’s helpful to consider how much these speculative images might end up reinforcing the stereotypical images the world would do well to depart from.

Editor's Note: This article was originally published on November 11, 2022.