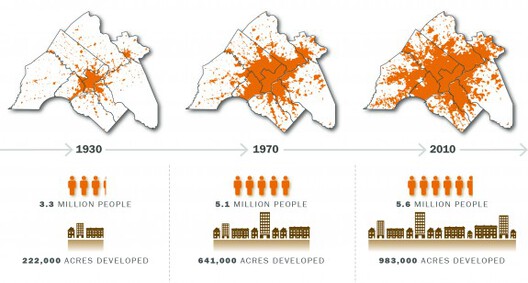

How we plan our cities, suburbs, and rural communities is a constantly evolving set of goals essential for creating sustainable cities. Not only do we need to consider what lies within these areas, but we also need to effectively design the boundaries between each, where urban meets suburban, and where suburban meets the small town. In recent years, urbanists have paid close attention to urban sprawl, or what sometimes happens when towns rapidly grow outwardly from city centers. What happens when cities seem to “sprawl” out of control, and are the design principals behind New Urbanism able to turn urban sprawl into equitable communities?

New Urbanism is a planning approach that emerged as an alternative to the urban sprawl patterns that became typical of post-World War II development. By reintroducing concepts to create walkable blocks, mid-sized housing, and amenities such as grocery stores, schools, and restaurants within close proximity, New Urbanism gives human-scaled spaces a place beyond urban cores. These developments almost resemble mini-cities, with rezoning policies that create diverse neighborhoods with a goal of being only a five-minute walk from the center to the farthest edge. New Urbanism’s ideals are captured within a manifesto that lays out its principles and goals for the future.

On the other hand, urban sprawl has largely occurred because of decentralized growth. While there is no singular definition, many people describe it either aesthetically or through street and housing patterns. Sprawl is the result of many socio-economic and cultural forces. For instance, over the last two years, we’ve seen people move out of urban areas to escape highly dense areas in favor of places where people can have more space, property values are lower, and the quality of commute tends to be better.

Urban sprawl costs the American economy more than US$1 trillion annually. Americans living in sprawled communities directly bear an astounding $625 billion in extra costs. And ALL Americans bear the other $400 billion more. Via @NewClimateEcon @LitmanVTPIhttps://t.co/LmByfyd3Nw pic.twitter.com/kLTTDBZltJ

— Brent Toderian (@BrentToderian) February 9, 2020

Many homes in these areas are low-density, single-family homes that sit upon small, carved-up lots, with private yards and winding cul-de-sac streets. Density in these areas is represented by median lot size, the number of homes in a given neighborhood, or the measured size of these single-family units. Urban sprawl areas also rely heavily on private automobiles, even for short trips, since these neighborhoods are not designed to be walkable. Many streets are disjointed and not planned in an easy-to-navigate grid-like pattern. These areas also feature “strip mall” developments, or “ribbon” developments, in which commercial properties and amenities all flank the sides of main streets and are fronted by massive parking lots. These malls are often comprised of grocery stores, convenience stores, large box retailers, and fast food chains.

Race has also been considered a factor in why urban sprawl is on the rise. The relocation of middle and upper-class residents from downtown areas is what is often called “white flight” and can lead to additional spread-out areas and lower property values within cities. In terms of age, younger families tend to move out to suburbs where they can live on larger lots in quieter communities. These areas are where people can afford the American Dream of homeownership in a low-density neighborhood.

Philadelphia, which had seen rather significant urban sprawl and outward development, took a new view on how to limit the boundaries for where people could move. Originally designed as a compact city confined by rivers to the east and west, the city’s initial expansion came in the form of industrial developments and small neighborhoods near them where residents walked to work. Many people did not adopt streetcars and rail lines but did find value in living farther away when paved streetways became more commonplace. Paired with private vehicular ownership, people began to leave the city center in favor of the suburbs. Over time, the city boomed with post-war housing and tax incentives which pushed people feather away. Now, to combat the rapid suburban growth, the city has established protected open spaces, where new homes or amenities could not be built. Instead, these protected areas were transformed into state and local parks, wildlife areas, farmlands, and conservation easements. Additionally, these smaller areas have explored ways to be less reliant on cars and public-transit dependent.

New Urbanism and other urban planning policies aim to reduce the negative impacts of unsustainable and arbitrary urban growth. By planning for spatial designs and anticipating future population growth, development can become more thoughtful, and land use more intentional. New Urbanism, with its emphasis on zoning previsions, growth boundaries, middle-sized housing developments, and walkable neighborhoods is one of the strongest frameworks we have to make urban sprawl more contained.

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topics: What is Good Architecture?, proudly presented by our first book ever: The ArchDaily Guide to Good Architecture. Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and projects. Learn more about our ArchDaily topics. As always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.

Editor's note: This article was originally published on September 27, 2022.