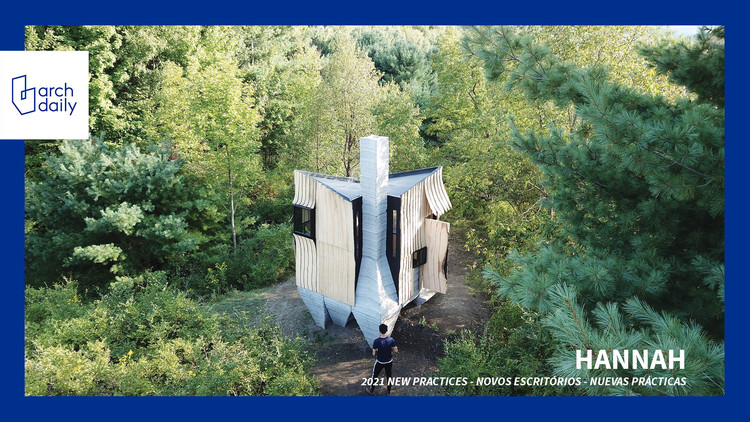

HANNAH Office is a US-based experimental research and design studio whose work focuses on advancing architecture and contemporary construction practices by examining the possibilities of new digital routines and fabrication technologies. Selected as one of Archdaily's Best New Practices of 2021, HANNAH Office was founded in 2012 by Leslie Lok and Sasa Zivkovic and constitutes a platform for exploring technology and material methods across a variety of scales, from furniture to urbanism in search of new design outcomes.

Leslie Lok and Sasa Zivkovic spoke to Archdaily about computational tools, the potential of robotic fabrication, as well as their academic work concerning digital construction technologies. Read the full interview below.

ArchDaily: Can you tell us more about HANNAH and how digital fabrication came to underline your body of work?

HANNAH: HANNAH is an experimental design and research studio working across scales from furniture to buildings to urbanism. We have a keen interest in architectural concepts related to making, materiality, fabrication, and construction. Those concepts are currently undergoing rapid transformations and paradigm shifts, fostered by technological, socio-economic, and cultural developments across the globe. We acknowledge that architecture’s processes of construction are rapidly changing and adapting to new realities. At HANNAH, we intend to reclaim authorship over these new processes of construction that critically influence the way we currently can build – or perhaps ought to build in the future.

In collaboration with our research labs at Cornell University, HANNAH builds open-source construction machines, which affect how we think and design through making. However, we do not obsess over technology for technology’s sake: as designers, we consider ourselves to be biased generalists rather than specialists. At various scales, our work’s performance and architectural expression are inherently derived from materiality, digital construction protocols, robotic routines, new technologies, odd construction techniques, and bottom-up design logic. At the same time, in a mix of means, it is inspired by precedent, history, program, ecological considerations, collective labor, personal obsessions, and the creative misuse of technology.

AD: What drives your material explorations? Is it the aesthetic possibilities, a search for a certain kind of tectonic performance?

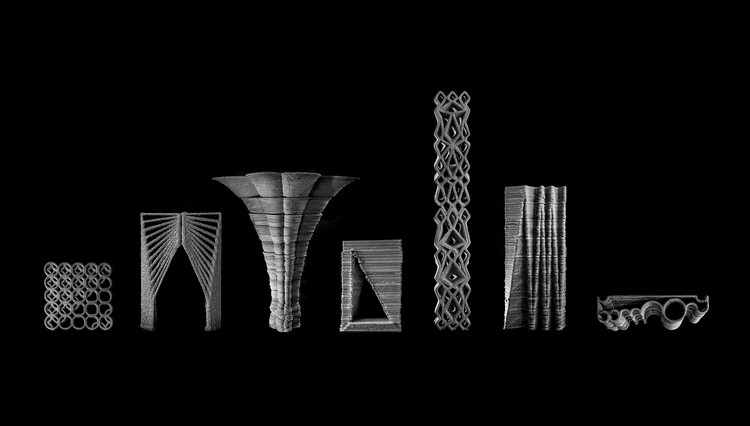

H: In the past several years, our work at HANNAH focused mainly on two material systems: concrete and timber. It is fair to say that we have a certain general affinity towards working with these two materials and their various hybrid configurations. For both material systems, we are interested in their aesthetic possibilities as well as their tectonic performance. Our work is driven by the tools and manufacturing processes we invent, modify, and utilize for our design projects. Those manufacturing processes come with certain design constraints as well as with unique tectonic opportunities. For example, we aim to optimize material usage and construction efficiency with the help of computational tools and iterative design studies in all of our projects. We use structural optimization protocols to reduce material usage in 3D printed concrete construction, such as in RCL’s research on SubAdditive 3D printing or we structurally optimize natural roundwood usage such as in RUBI Lab’s Timber De-Standardized.

Every so often, certain programmatic or aesthetic decisions outweigh the rational longings for efficiency and optimization, especially at the scale of a building – such as in the Ashen Cabin project. Ultimately, each of our projects intends to find its own and particular balance between architectural performance and design intuition.

AD: With this multilayered inquiry into architecture subjects, construction technologies, material methods, what does your design process look like?

H: Our design process is multi-faceted and its specifics strongly depend on a project’s context, the material system used, the available tools, and budget. We find enjoyment in working within the rules of numerous fabrication processes and material systems but we also try to push the boundaries of those rule-sets. In certain cases, we deliberately break those rules to enable the emergence of more intuitive design expression and creativity. Most of our projects at HANNAH creatively misuse technology in some form or another.

In more practical terms, our design process is often synergic and non-descript, moving freely between digital studies, simulations, code, physical models, writings, and sketches. It is important to point out that all our research and office projects are teamwork and that collaboration between our various teams and partners plays a critical role in our design process.

AD: What are some projects you’re currently working on, or ideas you’re experimenting with?

H: One of our main goals is to increase impact by scaling up our research investigations and by utilizing new and sustainable techniques of construction in building projects. Our initial research in concrete construction 3D printing started in 2015 and we have since completed a number of small-scale 3D printed projects such as RRRolling Stones, Additive Architectural Elements, and the Ashen Cabin. In the past two years, we shifted our focus from small-scale design-build projects to commercial projects with industry partners. These latest design efforts focus on the development of new models for 3D printed single family construction and mixed-use housing in urban areas. We think that 3D printing and automated construction will play an important role to make housing more attainable, affordable, and sustainable.

In addition to our interest in 3D printing technology, we have a strong passion for robotically-fabricated timber construction. In recent projects such as HoloWall, Ashen Cabin, or Log Knot, we use alternate material sourcing strategies, 3D scanning, and augmented reality technologies to work with wood which is commonly considered as waste. Our most recent project, Unlog, uses EAB-infested waste wood that is robotically sliced and playfully assembled into lightweight and unfolding structural components, stretching the limits of our architectural imagination – both literally and figuratively. The project will be on display in March 2022 at the Biomaterials Building Exposition at the University of Virginia (UVA), curated by Katie MacDonald and Kyle Schumann.

AD: How does your involvement in the academic field inform your designs? Moreover, what do you think is the relationship between academia and practice?

H: Our academic positions deeply inform our practice – and vice versa. We both teach at Cornell University where we direct independent research laboratories that advance our academic research interests. Leslie directs the Rural-Urban Building Innovation (RUBI) Lab that investigates building methods by coupling digital construction technologies with natural and non-standardized material for the design of adaptable buildings and housing in rural-urban contexts. By studying regional behaviors from spatial transformation to material resources, the lab contextualizes design strategies unique to local communities and seeks to develop impactful ways to rethink future urban construction.

Sasa directs the Robotic Construction Laboratory (RCL), a research group that focuses on the development of sustainable robotic construction technologies to advance our future built environment. Both labs develop fundamental research work that examines how novel digital routines can help to transform architectural design thinking across scales and material systems. In our advanced studio courses and seminars, teaching and research merge to inform pedagogical principles, introducing our students to new architectural paradigms in design and construction. The three entities – practice, research, and pedagogy – go hand in hand while retaining their distinctive formats for architectural exploration.

AD: What is the greatest potential you see in robotic construction technology?

The potentials of robotic construction technology are manifold. However, robotics-based construction technology is not a cure-all recipe to miraculously solve all of our collective challenges in architecture and construction. Applied within certain contexts, research shows that robotic construction tools and computation can help us to create substantially more sustainable and efficient buildings. Furthermore, architectural and manufacturing optimization can help save materials and can expand our access to new material systems, either through alternate sourcing of materials or through a complete re-definition of material intelligence. The ability to mass-customize architectural components, to make architecture more responsive, and to streamline construction processes is largely facilitated by new means of manufacturing. In that sense, robotic construction can help us to design and create better buildings.

H: Furthermore, working with new tools of construction enables us to explore new architectural languages and to discover unfamiliar forms of design expression. Construction methods and material systems – robotic or non-robotic – inform architectural form and space. Our tools enable us to expand on architectural precedents and build on the generations of work that came before us while simultaneously providing a certain freedom to re-think architecture from the ground up.

We invite you to check out ArchDaily's comprehensive coverage of the curated selection of 2021 New Practices. As always, at ArchDaily, we highly appreciate the input of our readers. If you want to nominate a certain studio, firm, or architect, for the 2022 New Practices please submit your suggestions.