The world is home to thousands and thousands of national parks – spaces allocated for conservation, hosting land usually left in its natural state for people to visit. The term “national park” itself differs in meaning around the world. In the United Kingdom, for example, the phrase simply describes a relatively undeveloped area that attracts tourists. In the United States, this terminology is a lot more rigid, describing 63 protected areas operated by the United States National Park service.

Within these parks around the world, architecture has sprung up – most often in the forms of lodges, projects which have sought to harmonise themselves within their immediate environment. The presence of a National Park “architectural style” is arguably most clear in the United States, which saw the development of a “National Park Service Rustic” style in the early 20th century, a style which valued non-intrusiveness over monumental architectural landmarks.

Working hand-in-hand with the field of landscape architecture, the ‘rustic’ style was made official with the publication of an architectural guideline for parks in 1918, which emphasized the fact that “particular attention must be devoted” to the harmonizing of new structures with the landscape. Even though the eclectic Arts and Crafts architecture had fallen out of style after World War I, architect Herbert Maier revived and incorporated the motifs from this architectural style twenty or so years later to great effect at Yosemite National Park, Grand Canyon National Park, and Yellowstone National Park.

Maier’s 1929 ‘Norris Museum’ at Yellowstone National Park was arguably the structure that fully set in stone the principles of what a rustic building should be. A combination of stone masonry and log construction as building methods served to make the building a secondary factor of the landscape, and not a primary element. Horizontal lines were also emphasised, a stylistic choice that would find its way into later examples of structures across the landscapes of National Parks in the United States

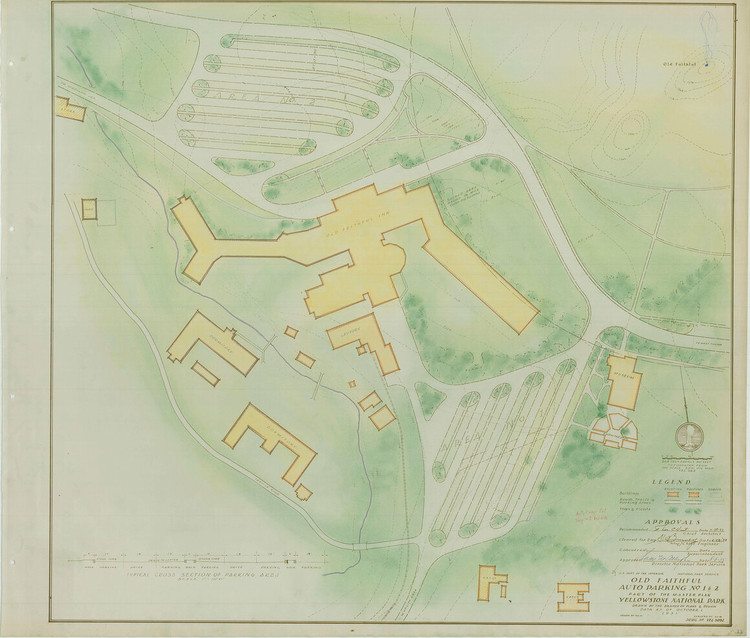

Notwithstanding the architecture of the individual structures housed in the National Parks, Landscape Architect Thomas Chalmers Vint can be credited as a key figure in the successful master planning of the National Parks in the United States. Assembling a team of landscape architects under him, Vint oversaw the assignment of districts to specific landscape architects, all of them undergoing extensive training in non-intrusive design under Vint’s tutelage. The masterplanning undertaken by Vint and his team thus made for a seamless coherence between stand-alone structures designed by architects such as Maier, and the surrounding landscape that the structures inhabited.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, the architecture of structures inside National Parks contains a diverse mixture of styles which draw from local vernacular but utilise modern materials. Kéré Architecture's National Park of Mali, for example, takes the local vernacular of local stone, and contrasts this with the presence of practical materials such as a stainless steel roof. In addition to this architectural design, the National Park also functions well on the urban scale, containing a pedestrian network which links the interventions dotted around the national park. Blending in with the environment in a similar vein to the ‘rustic’ architecture of the United States, the restaurant of the National Park follows the natural contour of the rock formation it sits on, making the building in its own way function as a secondary object.

The Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre by Peter Rich Architects, at the Mapungubwe National Park in South Africa is another architectural intervention in a National Park which seeks to blend in with its surroundings – albeit in a more monumental fashion. Undulating dome-like structures make up the building, with the dusty brown colour of the exterior stone merging in with the vegetation of the encompassing landscape. The complex design also features delicate walkways, following the gentle slope of the site.

The architecture of national parks around the world – pioneered in a way by the ‘rustic’ architecture of American National Parks, provides an interesting framework to help us understand the age-old question of building in harmony with the natural world.

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topic: Local Materials. Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and projects. Learn more about our monthly topics. As always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.