Social media is changing urban planning, facilitating the shift from a functional understanding of design to a formal and commercial one. Behind the friendly veneer of spaces conceived as sets for social media content, complex systems of surveillance are being tested and developed. The built environment turns into an attraction, populated not by citizens but rather by users who feel the need to self-document their lives. Public space disappears under the lack of agency and collective use, becoming a stage on which bodies move according to predefined rules and choreography.

For a couple of years now, Google Maps has been sending notifications to its users, signaling when there’s a cool photo spot nearby that they really shouldn’t miss. As we walk through a city guided by Google’s interactive map, or are tracked even when not using it, we are constantly reminded that our Instagram feed could really benefit from a panoramic view of hypermodern architecture. As architecture firms worldwide report designing spaces with the purpose of making them “Instagrammable”, we cannot help but wonder: How is social media shaping the public sphere?

SOCIAL MEDIA ARCHITECTURE

When The Broad museum opened in Los Angeles in 2015, it was immediately an Instagram sensation. You just couldn’t miss the “Instagram-worthy” new cultural institution, or the FOMO would be excruciating. Not only is the structure highly Instagrammable—consisting of honeycomb, off-white buildings with clear cut angles—but the art on display also works its magic, splashing its colors from the white walls like the perfect eye candy. The museum’s popularity grew so strong on Instagram that for the 2017 Yayoi Kusama exhibition it reported sales of 40,000 tickets linked to traffic coming from the app. Designed by global architecture firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R), The Broad seems to naturally make people reach for their phones to snap photos—both on the outside and the inside—as visitors take full advantage of the good lighting and art hanging around. The same is true for many of the firm’s projects.

One of DS+R’s recent projects is Moscow’s Zaryadye Park, which is routinely featured as one of the most Instagram-friendly locations in the Russian capital. The park includes a panoramic viewpoint that cantilevers 70 meters over the Moskva River, several pavilions, two amphitheaters, and a philharmonic concert hall. The social media hype around its sleek glass buildings which contrast with the surrounding greenery and the suspended viewpoint played an important role in attracting thousands of Moscovites and tourists alike—around 250,000 people turned up during the park’s opening week. Describing them as “purveyors of spectacle,” The Guardian architecture critic Oliver Wainwright acknowledged DS+R as being particularly enchanted by the power of Instagram.

.jpg?1591709312)

According to Wainwright, a number of architecture studios have gone as far as to admit that “Instagrammability” is now at the forefront of their concerns when working on new projects. In his words, Instagram has in fact become “one of the most influential forces in the way our environments are being shaped.” Many architecture firms are being quite open about this phenomenon: from public squares to private developments, from hotels to boutiques, every client is now requesting that they design with the Instagram feed in mind. What will prompt users of different spaces to share their photos on the app, and which hashtags will they be happy to use?

Instagram has rapidly become the go-to social media platform, with one billion active monthly users. Its highly visual nature pushes users to post curated snapshots of their lives, often encouraging them to look for stunning backgrounds that conform to precise aesthetics. Most of us would be familiar with these triggers just by being on the app: palm prints, rose gold accents, and marble surfaces for interiors; sleek and generic contemporary buildings of glass and steel with pops of color for exteriors. Graphic walls, both indoors and outdoors, prove to be another strong attraction, even an asset, for businesses that offer them as photo spots. Such spots are often written about in the media, with articles reporting detailed instructions of where to find them and how to best pose to get the perfect shot. One example among many is Los Angeles’ angel wing walls created in 2012 by artist Colette Miller as an interactive street art piece that quickly became one of the city’s most recognizable landmarks. Reflective surfaces are also popular, particularly when set in public spaces, with a famous example being Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate in Chicago. Contemporary art designs, encompassing large-scale, outdoor sculptures and museum pieces, often provide the creative and fun element that people seek to capture on their accounts.

.jpg?1591709323)

Businesses are taking full advantage of Instagram’s power to draw customers that want to recreate the experiences and pictures they have seen on the app. Australian studio Valé Architects, for example, even created an “Instagram Design Guide” which can be purchased from its website, alongside its design services which specialize in retail spaces, restaurants, and hotels. Arguably the most affected by the need to become Insta-worthy, commercial spaces are advised to make modifications such as offering a selfie wall, perfectly thought-out lighting, and suggestively tiled floors, just as the popular account and hashtag #ihavethisthingwithfloors continues to grow close to one million followers and posts. Think about the bathrooms inside Sketch, a restaurant in London, which features landmark eggy cubicles and a rainbow ceiling—or actually, think about the whole place, with its millennial pink soft chairs and David Shringley prints perfectly spread around the space. Some of these locations acquire such a status on the app that we all feel like we have to go there, to snap our own picture. Even the world famous department store Harrods is following the trend, hiring architect Farshid Moussavi to make entire sections of the space more Insta-friendly, according to Oliver Wainwright.

On a purely architectural point of view, however, these designs are being critiqued by architecture commenters—for example in this editorial published in The Architectural Review—because of the materials used, which are being chosen on the basis of their colors and feel rather than on how they will age or if they will be functional at all. Cladding that easily stains or peels, reflective surfaces that result in blinding spots, and shiny floors that become dangerously slippery with the tiniest drops of water are only some of the issues standing as testimony of what happens when architects prioritize photographability over function.

Nonetheless, the loss of functionality does not seem to concern social media architecture gurus. Valé Architects’ “Instagram Design Guide” credits a simple mechanism in determining why Instagram marketing is so successful: “I want to feel respected by people like me and those I aspire to connect with. I look for guidance of what I have to do and where to go to be part of that circle.” The firm’s strategy involves designing spaces that are “remarkable” for a specific customer target; one which they will consequently want to share with their peers. Both interior and exterior spaces should be set up to provoke a “visual sense of amazement, creativity, and fun.” People are different, but there’s a level of predictability to these feelings, and there’s specific design concept that continues to prove very popular on Instagram, year after year. Locations that inadvertently become “Instagram sensations,” such as Bali’s rice paddies or Hong Kong’s high-rises, are now becoming an exception in a world where places are constructed to look photogenic by design.

.jpg?1591709334)

Not only is this affecting the look of our built environment, but it is also modeling our lives and affecting how we plan our days and look at our surroundings. There’s an entire genre of YouTube videos, as well as online articles, dedicated to sharing the most Instagrammable locations to visit when on vacation—and these lists often involve locations that became Insta-worthy by accident. Housing complexes and once hidden spots in the countryside become tourist sites through this word-of-mouth 2.0, resulting in private grounds being inundated with people looking for the perfect photo opportunity among pastel-shaded colors, lush nature, and panoramic viewpoints—much to the annoyance of local residents. Even Ryanair is publishing articles such as “Europe’s 17 most Instagrammable cities,” placing—perhaps unsurprisingly—London, Paris, and Rome in the top three. Most of us probably don’t entirely plan our holidays according to our social media posts, like influencers do. But we are all familiar with going through our days thinking about what we can post as we look at places, food, and landscapes with our Instagram stories and grid in mind, and go out of our way to think about funny captions, to create still lifes of objects, and to compose our life so that it looks appealing.

However, the search for photogenicity, for the show over reality, should not be simply considered a symptom of the progressive aestheticization of society, but a reaction to the current social and political crisis. As noted by writer and activist Carmen Pisanello, social media kickstarted the blurring of distinctions between mass cultural experiences and elitist ones—which is definitely not substantial, as it’s based more on the creation of a shared glossy imaginary rather than a real reduction of the gap between the two. Social media also acts as an emotional booster. While promoting a rhetoric of fear and hate on one hand (i.e. Facebook comment sections or Twitter witch-hunts), it also offers us an aesthetically perfect world where we can hide to forget our fears and everything that doesn’t align with this aesthetic (i.e. Instagram, as well as Pinterest’s dream-like boards). To match this ideal of a picture-perfect society, it becomes necessary to sanitize and normalize public space, removing all that is considered abnormal, extraneous, or inappropriate from sight. Marginal subjectivities are part of a social and economic system that constantly rejects them, trying to expel what it fails to integrate and what does not align to a certain disciplinary conduct.

Recalling Pisanello, the psychological refusal of elements and bodies that are not integrated in contemporary society doesn’t result in self-analysis or political debate, but rather in aesthetic denial. From millennials’, attachment to highly aesthetic, pastel-colored, and soothing environments, we can glimpse a direct reaction to the lack of future prospects, solidity, and financial/political security that characterizes our current society. Growing up in a seriously troubled world, “millennial pink” responds to our need to be reassured and to de-problematize the bewildering reality in which we are immersed.

MILLENNIAL PINK CONTROL

The pervasive and ubiquitous Internet of Things (IoT) forms the core of the “smart city,” defined as “a place where traditional networks and services are made more efficient with the use of digital and telecommunication technologies for the benefit of its inhabitants and business,” in the words of the European Commission.

Thinking through the definition, we can unpack who’s really benefiting from these technologies. Sure, some of us might feel safer in a surveilled environment, or appreciate when surrounding objects send notifications to our mobiles inviting us to take a photo or discover nearby points of interest. Most of us, in fact, are happy to have our movements tracked while following Google Maps or getting an Uber. We willingly share plenty of sensitive data just by using social networks, and even more so by posting on them. Very recently, an apparently innocuous game known as the “10 Year Challenge” has become an important global case concerning the ability of social platforms to willingly deceive their users into unwittingly taking part in the development of AI technologies. As reported by journalist Kate O’Neill, the challenge was perfectly sugarcoated to produce a clean set of biometric data that could be used to train facial recognition algorithms, on which companies such as Facebook and Amazon have been working for years. Pulling information from a variety of databases and social media networks, these technologies are used and tested by governments and companies with the aim of collecting data on individuals, as well as monitoring and profiling deviant elements within society. While the purpose of IoT technologies and apps is to improve our lives, prevent problems, or simply manage the flow of people within large cities, a number of civil rights groups have raised concerns about the objectives and consequences behind widespread data collection and algorithm-based programs.

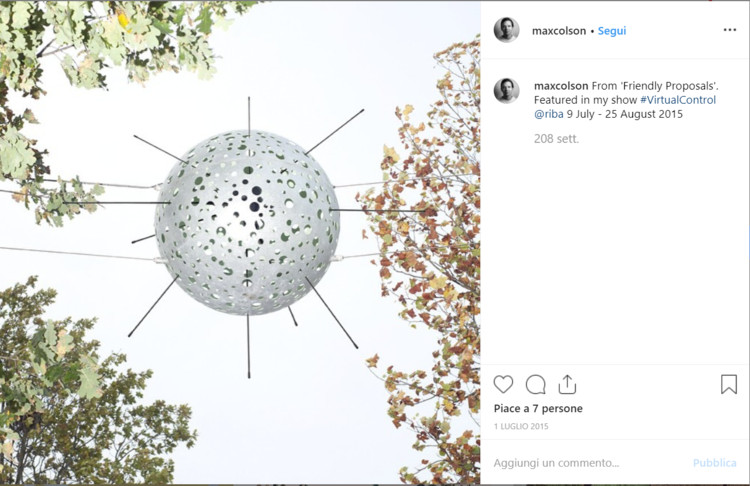

The same practice takes place in urban environments increasingly designed to look sleek and Instagrammable, as controlling devices often put on attractive masks. We are used to widespread CCTV on city streets and in public transport, retail spaces, parks, and virtually any other environment—yet we are still unfamiliar with thinking about the objects around us as more than what they look like, as active subjects collecting data from us and interacting behind our backs. In his series Friendly Proposals For Highly Controlling Environments, British artist and photographer Max Colson walks us through the hidden surveillance equipment at London’s Olympic Park. Lamp posts can record noises and communicate with CCTV when hearing unusual sounds; rubbish bins detect passing smartphones and their movements, while the trees are equipped with decorative structures disguising tiny antennae. As urban and rural space is increasingly owned by global development corporations and the internet is being controlled by a few powerful companies that get to decide the design, uses, and even infrastructure of digital technologies, millennial pink walls, tiled floors, and steel surfaces become the perfect hideouts for privatization processes involving the internet and physical space in a very similar way.

In an article published by El Pais, architect and curator Mariana Pestana notices how the feelings of powerlessness and dissatisfaction that many of us share come from a lack of ownership of the communication tools we use. This is so deeply rooted that even when we purchase a smart surveillance system for our homes and properties, it can play tricks on us. In the ongoing series Self Portrait From Surveillance Camera, artist Irene Fenara presents us with a collection of unusual “selfies.” After finding the location of smart cameras online, she travels to “take” her shots in front of them and then quickly hijacks their system to save them, as such “photos” are typically deleted 24 hours later. The key to this work is that smart cameras are not in a closed circuit anymore, but rather connected to the internet. Many users who purchase these systems don’t realize that by not changing the standard password that comes with their devices, anyone can enter their system and potentially spy on them.

As humans, we have the flexibility to become integrated with objects, tools, machines, and digital technologies. Our physical bodies, and their receptiveness, are a fundamental link between social media, devices, and spaces. We become part of a complex network in which we are one actor among many different non-human actors which are dictating and influencing our moves—in the same way that we are making their functioning possible by designing them a certain way. A smart bin is collecting data on our rubbish, an antenna on a tree listens to us, and Instagram sends us notifications because we haven’t posted in a while. The boundaries between subjects, time, and space are crumbling as we populate our surroundings with IoT agents. In the words of Donna Haraway, “Our machines are disturbingly lively, and we ourselves frighteningly inert.”

FROM PUBLIC SPACE TO MERE PHOTO OPPORTUNITY

In an interview published by Domus, Dutch architecture practices UNstudio and OMA/AMO discuss the consequences and possibilities of Instagram for architecture, going as far as using the social media app as a way to monitor how buildings are used and experienced after completion. Referred to as “post-occupancy analysis,” this evaluation is routinely carried out through interviews and surveys. In 2015, OMA/AMO launched the hashtag #omapostoccupancy, making Instagram a primary tool in its process of gathering understanding of how people use and appropriate buildings. In the words of Giacomo Ardesio, architect at OMA/AMO: “The more a building is capable of engaging somehow the visitors beyond the program that it is meant to solve, at least from a certain point of view, the more it is successful today.”

It is indeed admirable when the built environment propels people to dwell and engage in ways that go beyond its immediate function(s). But by evaluating the use of architecture through its representation on Instagram, we are validating the reduction of public space to a good background for pictures, together with the flattening of architecture to its images. If a housing complex appears in plenty of Instagram shots looking like a popular location, then there is less need to think about the inhabitants’ needs. The success of that building will be evaluated as a photo opportunity rather than a place that is lived in and used everyday by people with specific needs, first and foremost their privacy. Within this framework, certain locations emerge thanks to the intersection of popularity and quantity of data produced, bringing about a new geography of consensus which excludes everything that is not considered aesthetically pleasing in terms of “good content.”

The hashtag #omapostoccupancy helpfully demonstrates the important role that Instagram increasingly plays in the production of contemporary spatiality, heavily influencing how architects think about space and how people experience and move through the physical world. Urban planning—and space organization in general—greatly contributes to producing and structuring our bodies and the ways we inhabit and move through space. As individuals, we are increasingly planning our outings based on the Instagrammability of the locations that we are going to visit, but the greater risk is to produce an idealized image of a public sphere that is easily eroded when confronted with factual social issues. “Selfie politics are attention politics: it is all about who gets to be seen, who gets to occupy the visual field,” writer Rachel Syme wrote. Contemporary outside space is not a place where outsiders can feel situated. When “Instagrammable” is the main preoccupation of clients and designers, they are actively investing in a sleek and sanitized version of space, cutting out all of its possible transformative and imaginative potential.

Geographer David Harvey’s work is a powerful tool to shed light on what has been happening. With the rise of global development firms actively financing and lobbying to launch a multitude of regeneration projects, the privatization of public space is extremely widespread; not only does it install on existing structures, but it is also not limited to private partnerships that characterized neoliberal urban governance in the past decades. It goes as far as to directly contribute to the design of urban areas, modeling new forms of life and sociability. We can take the renderings as the perfect example of what this looks like: wealthy and mostly white human figures leisurely stroll, shop, and take photographs against fake architectures which look exactly like the digital models once completed. Under these conditions, ideals of urban identity, citizenship, and a true sense of belonging become much harder to sustain. Even the idea of a city being a collective political project gets easily forgotten in the swamps of neoliberism, as quality of life becomes a commodity for those with money; those who can gain access to the hyper-surveilled, sleek-looking attractions on offer.

A rapidly growing corpus of scientific research now links severe conditions such as depression and anxiety to a widespread use of social media—Instagram being the most triggering of them all. Social networks are the perfect substitute for a crumbling collective sphere, particularly one that is rooted in urban space. These webs are tight enough to give us a sense of belonging, rewarding our brains with their system of likes and hearts, while at the same time giving us anxiety and the additional work of putting out good content to keep the mechanism going. Their addictive functioning starts penetrating our daily lives until we start seeing the world, and even designing it, according to their schemes. Calling in philosopher Zygmunt Bauman’s seminal concept of “fluidity,” it is the falling apart, the friability, the brittleness, the transience, the until-further-notice of human bonds and networks which allow these powers to do their job in the first place.

In the words of British architect Farshid Moussavi, “Instagram is reinforcing the fact that space matters, which can only be a good thing for designers and architects.” While this is definitely true in terms of more business for architecture and interior design studios, as both public and private spaces are in need of more frequent refurbishments to keep up with the pace of social media trends, it is worth reflecting on the role of designers. It is true that architects have been designing photogenic buildings for a while now, and that social media architecture may represent an extension of the “Kodak moment.” However, isn’t it just being reduced to a backdrop provider, ultimately flattening the world into a giant selfie stage? We could say that Instagram is encouraging more people to go to art exhibitions and to pay attention to their surroundings. But we could also argue that when people go somewhere with the intention of posting about it on Instagram, the app is controlling how they plan their day—even down to their outfit or makeup—and how they will interact with the chosen physical space. Our interactions become less spontaneous and our experiences more homogeneous as we plan our outings for “content.” Looking for a specific aesthetic experience, we standardize our way of seeing places and are less prone to interacting with space that is challenging, or just different. We wander less outside our comfort zones and lose spontaneity in our paths and interactions through the city. As social media architecture aims to construct this new glossy and frictionless world, where will we locate ourselves?

This article was originally published on Strelka Mag.

.jpg?1591709312)

.jpg?1591709323)

.jpg?1591709334)