As part of ArchDaily's coverage of the 2016 Venice Biennale, we are presenting a series of articles written by the curators of the exhibitions and installations on show.

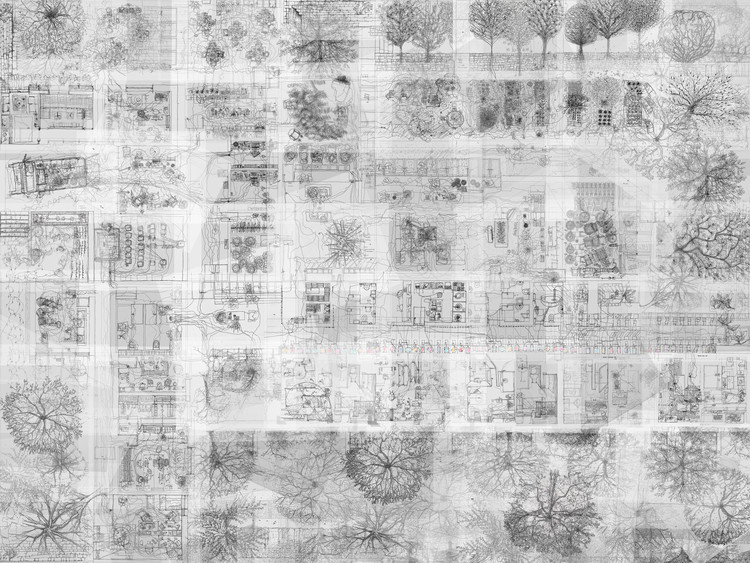

Our report is a reflection on the lessons learnt through designing and revisiting buildings for people with dementia. Visitors enter our space at the end of the Arsenale through a gap in the partition walls. The room is darkened, in contrast with the projected brightness on the floor. The floor accommodates a 4.8m x 6.4m animated drawing of the Alzheimer’s Respite Center. The drawing is dynamic, with multiple projected hands moving across the plane of the floor as they create fragments of a plan. They merge and overlap. These hands represent sixteen individuals inhabiting a series of rooms at the Alzheimer’s Centre. The projection consistently labours towards the clarity of a completed plan but falls short of achieving it.

Suspended speakers create a soundscape, consisting of the physical sounds of the act of drawing itself, layered with murmured conversations; sounds of rain and the sea; quotidian noises—a kettle boiling, children playing, people eating—and the bells of the Angelus.

This installation is an attempt to communicate and interpret some of the changes to spatial perception caused by dementia. In order to understand these changes, we have read, researched and questioned. We have spoken to a broad range of people—neuroscientists, psychologists, health workers, philosophers, anthropologists, people with dementia and their families—about dementia, the brain, and the role of design in dementia care. These conversations are recorded on our website.

We are interested in the social function of architecture: how it can improve the lives of people with dementia. Beyond this, we hope that our research into the impact of the condition on spatial cognition will equip us with a deeper understanding of how all of our minds interpret space.

Our project has also highlighted the shortcomings of the traditional architectural plan: an inhabitant may never experience the building from the architect’s complete and fixed vantage point. This disconnect is particularly apparent if the inhabitant has Alzheimer's Disease, and has lost the ability to use memory and projection to see beyond their immediate situation and create a stable model of their environment. Our projected animation attempts to address this, by working to develop a technique for drawing the building from the perspective of inhabitation.

The process has been collaborative, enlisting the skills of an animator, a composer, AV experts, graphic designers and many drafters. We have consulted people with dementia for feedback on the website design. We have been planning, testing and adapting our drawing technique with our drafting collaborators. At times, we have needed to design tools of production, such as glass tables for recording the drawing process. We have had to accept a certain level of unpredictability and uncertainty regarding the finished product, perhaps as a consequence of attempting to represent a cognitive state which is only partially understood, using a medium that we are developing through iteration and experiment.