The Architectural Guide China is a travel book which covers cities primarily located on China’s eastern coast. These cities—such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Hong Kong—have become centers for forward-thinking urban design and architecture. The guide offers maps, drawings, photographs, historical background, and essays describing Chinese architecture at all scales – ranging from small temples to the organization of major metropoli.

Based on the authors' experiences of directing study abroad trips throughout the country, Evan Chakroff, Addison Godel, and Jacqueline Gargus, have carefully curated a selection of contemporary architectural sites while also discussing significant historical structures. Each author has written an introductory essay, each of which contextualizes the historical and global socioeconomic influences, as well as the stylistic longevity of the chosen sites in this book. One such essay, by Chakroff, has been made available exclusively on ArchDaily.

Here ArchDaily presents an excerpt of "Scalelessness: Impressions of Contemporary China," the book’s introductory essay by author Evan Chakroff. In it he summarizes his “scaleless” sense of Chinese architecture by identifying various urban planning designs throughout history.

Introduction by Kaley Overstreet

Scalelessness: Impressions of Contemporary China

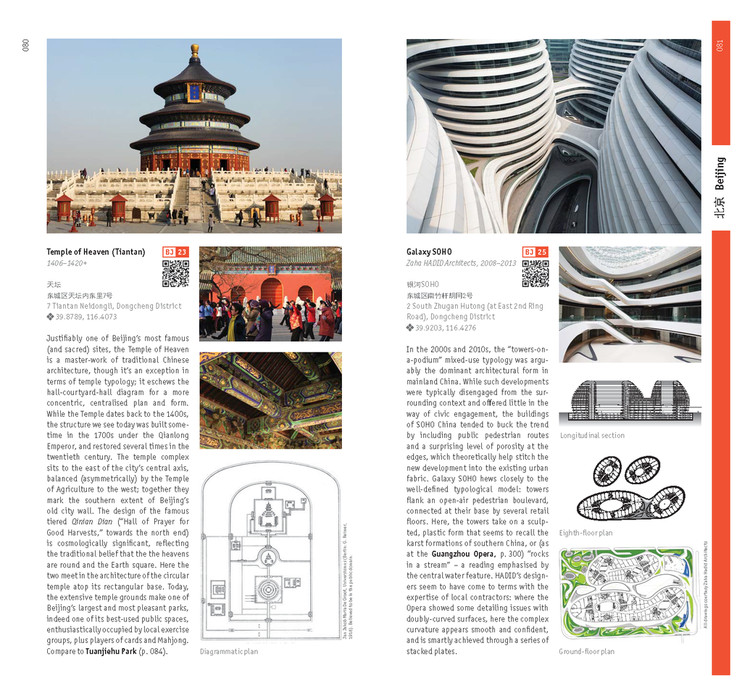

In an era of accelerating population growth, mass urbanization, and ever-increasing pressure on natural resources and the environment, architects and urbanists have a responsibility to study the megacity in depth, to see first-hand the advantages and challenges associated with these massive urban agglomerations in order to better understand what will be the dominant urban form of the coming century. Nowhere is the megacity phenomenon more prevalent, or more accessible, than on China’s eastern coast, where we find ample evidence of the ‘economic miracle’ of the ‘reform and opening up’ era. While all buildings are born of their distinct historical context, the general urban condition here can provide lessons for designers the world over. Each city has its own distinct history, whether as a dynastic capital, regional trading centre, global mercantile powerhouse, or foreign colony. Each has been affected profoundly by China’s recent economic transition, and by studying each in turn we can begin to construct models for rapid urban growth that are applicable to other contexts.

If the next one hundred years will indeed be known as “the Chinese century” it will likely not be due to China’s dominant economic position, or its military power, but because China’s contemporary urbanism has become a global model that countries and cities across the economic spectrum seek to emulate. Already, new towns are being built in Africa on Chinese models, backed by Chinese investors.1 The dominant mixed-use commercial typology – towers on a podium – has already gained traction from Kazakhstan to Kansas. There is perhaps no better architectural representation of our contemporary world: these projects are massive in scale, disorienting in urban configuration, socially and economically stratified, and often overlaid with myriad media layers in the form of integrated advertising, electronic augmentation, ubiquitous surveillance, and location-aware digital social media. The scalar shifts and formal ruptures we find in China’s contemporary urban morphology can be read as a physical manifestation of our disjointed, fragmented social fabric.

In our hyper-connected world, there is no “Chinese architecture” any more than there is a single European or American style. While this essay deals with architecture in China, governed in part by local codes, the phenomena identified here – namely scalelessness, fragmentation, and inauthenticity - can be found world-wide. Where Western observers often label contemporary Chinese architecture as insensitive, oversized, or inhumane (even totalitarian), in each case there is a global precedent. Projects we find odd (or even offensive) can be rationally explained as originating in specific socioeconomic historical circumstances, and shaped by a global cultural context. Ultimately, architectural examples from contemporary China can be used to elucidate some aspects of today’s worldwide socioeconomic trends.

A quality of scalelessness has long played a role in Chinese design practices. Scalar shifts, juxtaposition, and spatial layering (devices we may think of as modern inventions) are all in evidence in Suzhou’s classical gardens, dating back centuries. In the gardens, visitors are encouraged to wander. Garden paths often take the form of covered walkways, passages that slip between buildings, or bridges that pass over tranquil ponds. The experience of the Chinese garden is one of near constant delight, as different structures frame and reframe views of the architecture and landscape in surprisingly different ways from each vantage point. Often, one will catch an oblique glimpse of a distant rockery through several layers of screens and windows, only to later arrive in that space to find that the rockery is a radically different size than anticipated. This perceptual trickery is one of the classical gardens’ greatest pleasures. It is also a key component of China’s traditional arts: this ambiguity of scale, and emphasis on relativistic perception is essential to traditional landscape painting, where narrative progression and shifting perspectives animate the ‘reading’ a painted scroll. The taihu stones found in most gardens work in similar ways, appearing abstract or figural depending on viewing angle, and views of the full object in context are often denied by successive layers of architectural elements. In the art of penjing (the Chinese precursor to bonsai), miniature landscapes in small trays are often staged deliberately to draw comparison with framed views of ‘real’ landscapes in the garden, beyond or its walls as ‘captured views.’ Both taihu stones and penjing trees represent a kind of synthesis, at once natural and artificial, that hints at concepts of authenticity at odds with Western traditions. Walking through the classical gardens of Suzhou, or viewing a landscape painting, one is left with the impression that scale is relative, fluid, and malleable.

This impression is only enhanced when we consider China’s traditional architecture and urban planning. In pre-modern, dynastic China, many structures followed the same typological diagram, the siheyuan courtyard home. While many ancient cultures developed courtyard-based residential typologies (the Greek/Roman peristyle court, for instance), in China the basic arrangement of four (si) halls around (he) a central yard (yuan) formed the basis for everything from homes to shops and offices, to government complexes and elaborate palaces. Although the scale varied widely, all were based on the same courtyard diagram. In the siheyuan, climatic, social, and cosmological concerns merge in a single design. The residential typology, in its simplest form, consists of a perimeter wall enclosing one or a series of courtyards, flanked by halls oriented to the cardinal directions. Formal entry was typically from the south, and the residential compound was encoded with a Confucian hierarchy, with the older generations residing in the best-appointed rooms to the north, and younger members of the extended family filling the other halls in a specific arrangement dependent on gender and birth order. The halls tended to be more open to the south and closed to the north, a concession to feng shui that serves environmental purposes well, blocking northern winds, and catching the low sun in winter.

Recent major “civic” projects (like CCTV, the National Theatre, and the National Olympic Stadium), are characterized by their massive size, true, but each exists as an independent object in a field, an urban sculpture with no detail betraying the relationship to human scale. They seem intended to be viewed from across town (smog permitting), from varied and multiple vantage points, much like the landforms in traditional landscape painting. While the designers of these projects sought to create cultural icons representative of an empowered nation, other developers chased after more easily-measured superlatives. The race continues, with the mega-tall Shanghai Tower now complete, and Shenzhen’s Ping An Finance Centre soon to overtake it as the world’s second-tallest skyscraper6. Chendgu’s Century Global Centre, meanwhile, claims status as the world’s largest building by floor area, its 1.7 million square metres containing an enclosed mall, a waterpark with indoor beach, numerous hotels and restaurants, a recreation of a Mediterranean village, even, allegedly, an artificial sun.

To outside observers, the scale of these projects can be shocking (as can the speed and danger of construction), but rather than ascribe the frenzied construction to something inscrutable about the Chinese character, we can find historical precedent both in China and abroad, and view the current wave of megaprojects in their proper historical context. As in the past, these massive feats of architecture and engineering are most often built as representations of power, with each superlative achievement wielded like a trophy. The vast scale of China’s urban landscape can be disconcerting, but it flows from China’s long history, in which large building complexes were symbolic of the dominant power of each age. The spatial and scalar gradient between these and the vernacular residential blocks has been a normal condition of China’s urban morphology for centuries, if not millennia.

In the 2000s, foreign architects’ attempts to mitigate this fragmented condition were largely unsuccessful. The original design of OMA’s CCTV featured an internal public ‘loop’ that would pass by television studios and offices, revealing the process behind the production of the day’s news, and, in theory, increasing transparency and accountability for this state-run media conglomerate.16 In practice, the public loop was cut from the design (or perhaps survives, off limits), and today the building is surrounded by a secure perimeter fence, and accessible only to those with the proper credentials and connections. The “Bird’s Nest” National Stadium seems to have a similar social ambition, as access to the stadium was to occur through a field of canted columns. With no monumental entrance or predetermined entry sequence, the vectors of public access were to be as random and free as the façade’s structural pattern. Today, the stadium is fenced off, accessible via several entry gates for ticketed visitors. Beijing’s Linked Hybrid, intended to engage the surrounding blocks with numerous entry points, finds its ‘porous’ perimeter sealed with a long wall capped with a traditional Chinese tile roof. Even Urbanus, who have made accessible, public space a top priority in their work, find themselves hemmed in: see the unfortunate fence at Luohu Art Plaza, or the walls surrounding the Maillen Hotel & Apartments; both projects seem to push for greater connectivity across boundaries, only to be denied at the perimeter. It’s tough to call such appealing buildings failures, but in each case the architects’ social ambitions have been stymied by the forces that compel clients and owners to wall off these complexes from their context. Though knowing China’s urban history, this should come as no surprise.

Chinese architects today tackle the incomprehensible challenge of engaging with the nation’s long history, modern disruptions, and contemporary ascendance with admirable aplomb and keen aesthetic sensibility. To take one example, Pritzker Prize winner Wang Shu’s firm Amateur Architecture completed the Ningbo History Museum in a second-tier city far from international scrutiny. The site planning aligns the museum’s rectangular floor plate in a symmetrical arrangement with several other major civic structures in a new district. The museum faces the central plaza of this new city centre, and forms one of the four “halls,” if we consider the new CBD as an inheritor of the siheyuan urban typology. The Ningbo museum acts as a sculptural object in the landscape, but its form is more complex than just that: at the upper level, the volume is carved away to create pathways and staircases, and impromptu auditoria, and at the upper, accessible, rooftop level, the sharply cut forms of the building start to resemble factory sheds and rural houses. The museum is at once a massive civic venue aligned with a capital-socialist CBD master plan, and a celebration of the rapidly-vanishing exurban village typology, both in material quality (through reclaimed bricks) and in spatial organization.

AI Wei Wei’s Archaeological Archive is more explicitly narrative in its design. The artist’s skill as a sculptor becomes apparent as one orbits the building, which offers up multiple, often contradictory associations from different vantage points. From one end, the elevation is the ideal of a simple farmhouse (or perhaps a primitive hut), nestled in overgrown grassland. Moving around the building, the profile extrudes and elongates into an industrial shed. Further around, the sunken plaza reveals a mirror-image of the ‘ur-house’ and confirms its geometry as an imposed, hexagonal, geometric order. Continuing around, the house profile is re-established, now undercut and destabilized by the ‘excavation’ of the sunken plaza adjacent. Reading the pavilion from this cinematic sequence of views, we can conclude that accelerating modernization has literally stripped away the foundation of traditional society, a commentary on architecture’s role in a rapidly changing culture.

These complex ideas emerge in projects that, simultaneously, demonstrate the architects’ deft understanding of the various groups their projects serve: their financiers, the public, and the global architectural press. Where foreign firms viewed China as a tabula rasa and designed accordingly, Chinese designers are charting a new path that shows a deep appreciation for historical traditions, while still accepting the potentially radical nature of a design culture that eschews material authenticity. Their keen observation reminds us that the world is defined by coexisting constituencies that are spatially contiguous but separated by invisible socioeconomic boundaries. Such radical juxtaposition is physically and visually clear in China, but the cultural divisions exist throughout the world. Ours is not an era of boundless transparency and democracy, but one where society exists as an intricate web of relationships, and one’s access to the varied planes of society is limited by one’s connections and place within the global hierarchy.

Though this conclusion may be distressing, there is hope yet. The qualities of contemporary urbanism identified above apply equally well to the hyper-real, digital space of ‘the Cloud.’ Online, there is no physicality, no historicity: the hypertext web is infinitely fragmented and discrete, and the question of authenticity is moot in a virtual space where all cultural production is reduced to bits of raw data. Urbanism, of course, pre-dates the virtual layers we find augmenting our physical experience of the city, but could life in the contemporary city still be seen as an analogue of this digital commons? Could the experience of navigating the disjunct city prepare rising generations for the digital-hybrid public ‘space’ we find emerging before our eyes? When considering the role of the city in politics and society, we must also consider the digital layers now overlaid on physical space. As a coda, consider two final examples.

In late 2014, the “Umbrella Movement” protests swept Hong Kong for months; a continuation and intensification of long-standing dissent in opposition to Beijing’s increasing political control over the SAR. While the protests began in the forecourt of the HKSAR Government Headquarters, they soon spilled into the streets of Central and, later, Mong Kok, across the harbour. Blocking major highways, the protesters soon arranged themselves into micro-urbanisms, established food distribution networks, set up ranks of study carrels, founded ‘residential’ zones lined with tents, etc; ‘occupying’ Hong Kong’s major arterials. Meanwhile, a parallel protest played out online through location-aware mobile apps that were able to bypass government firewalls and signal disruption. The emergence in Hong Kong of the “Great Firewall” is unfortunate, but like its physical namesake, it is a barely-secured patchwork. There are always ways around the wall.

While the Hong Kong protesters politely asserted their right to democratic elections and the right to a physical space for civil discourse, Ai Wei Wei staged a protest of his own, remotely exhibiting “@Large” at Alcatraz, while under house arrest in Beijing. The ironically titled and digitally-inflected show engaged directly with themes of incarceration, freedom, and, ultimately, the state of the world as both infinitely expansive, and oppressively intimate. Increasingly, this digital-physical bifurcation is thematized in Ai’s work which - while exhibited widely - will without doubt be experienced more often through digital screens than through physical proximity.

We can consider China’s nascent hybrid digital urbanism as a new form of public commons - but one still divided along socioeconomic lines, with every different group barred access from certain enclaves, and admitted to others. These limits and boundaries, though present, are kept mostly hidden in the United States and the Western world, but in China, both the physical and virtual dimensions of segregation is plain to see. Barriers, checkpoints, fences, walls, and firewalls all serve to dispel the pretence of an increasingly open society. The modern Chinese city allows the existence of multiple, disparate ontologies in the same physical space. Today hyper-capitalism is married to a watered-down authoritarian socialism. For “both-and” there’s no better example than China.

If architecture is to be a reflection of society and a physical manifestation of a civilization’s hopes and dreams, then there is no better representation than the architecture and urbanism of contemporary China. Architecture is a kind of calcification and fossilization of civilization, a permanent record with each architectural age representing the ambitions and dreams of the era. No place on earth better represents today’s globalised, media-saturated culture than China’s coastal megacities.

Footnotes

[1] Michiel Hulshof and Daan Roggeveen. “Go West Project”

[6] As of this writing, the Council for Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat lists the top three tallest completed buildings as Dubai’s Burj Khalifa (828 m), Mecca’s Makkah Royal Clock Tower Hotel (601 m), and New York City’s One World Trade Centre (541.3 m). Shanghai Tower recently topped out at 632 m and the Ping An Finance Centre is set to reach 660 m when completed in 2016, though both will soon be surpassed. http://skyscrapercenter.com/buildings

[7] Of course grand projects are common to all civilizations, but China is unique in that building morphology of such complexes has undergone continuous refinement over thousands of years. Note, for instance, the persistence of mortuary typologies, from the earliest Qin Dynasty tombs (p. 397), through to twentieth century monuments like the Sun Yat-Sen Mausoleum (p. 133), or the survival of the basic layout of administrative compounds

[16] Koolhaas: “A public loop offers visitors access to all major components of the building.” Newsweek