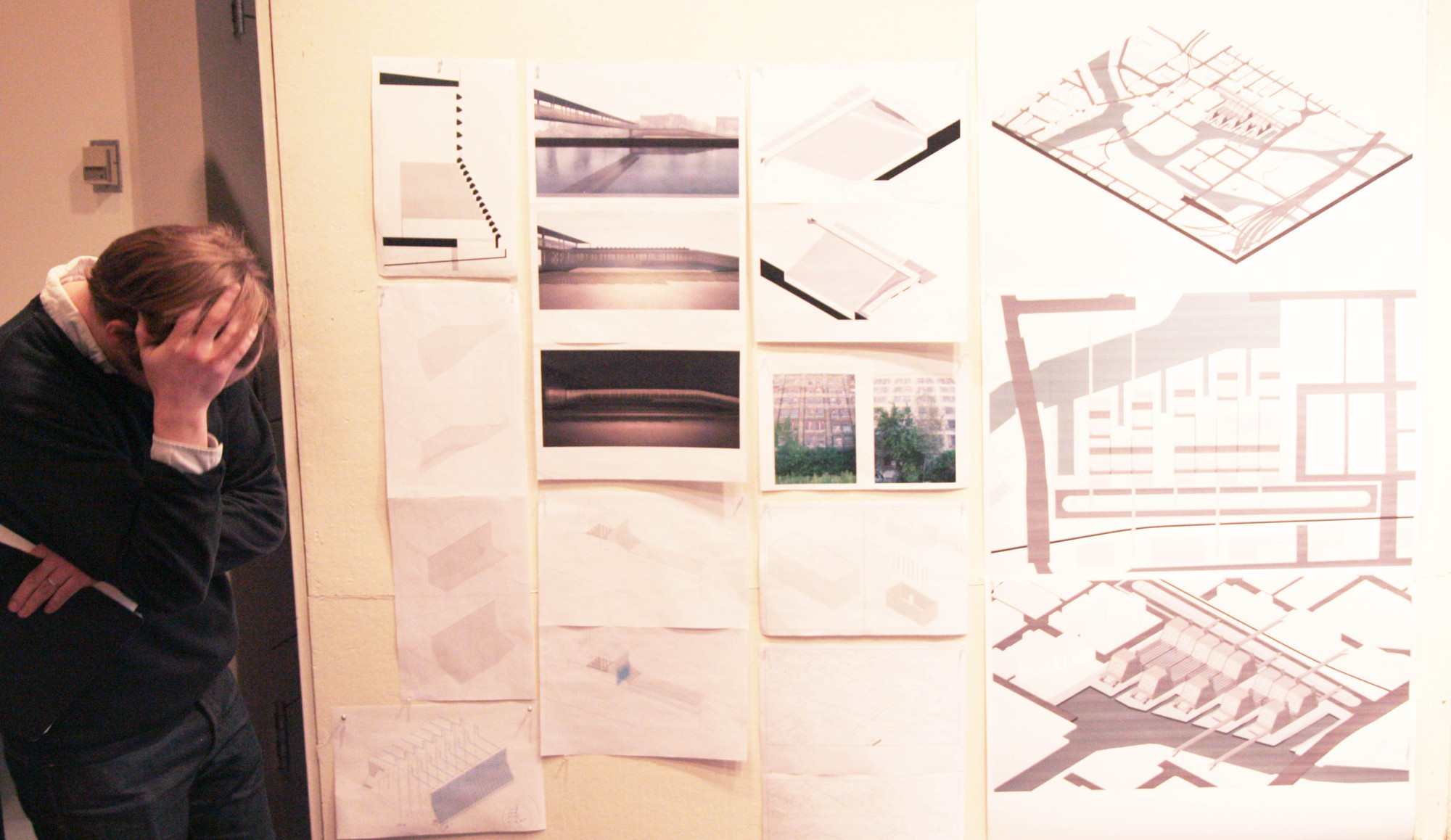

In a recent article in which ArchDaily reached out to our readers for comments about all-nighter culture, one comment that seemed to strike a chord with many people was kopmis' assertion that, thanks to the tendency for professors to "rip apart" projects in a final review, "there is no field of study that offers so much humiliation as architecture." But what causes this tendency? In this article, originally published by Section Cut as "The Final Review: Negaters Gonna Negate," Mark Stanley - an Adjunct Professor at Woodbury University School of Architecture - discusses the challenges facing the reviewers themselves, offering an explanation of why they often lapse into such negative tactics - and how they can avoid them.