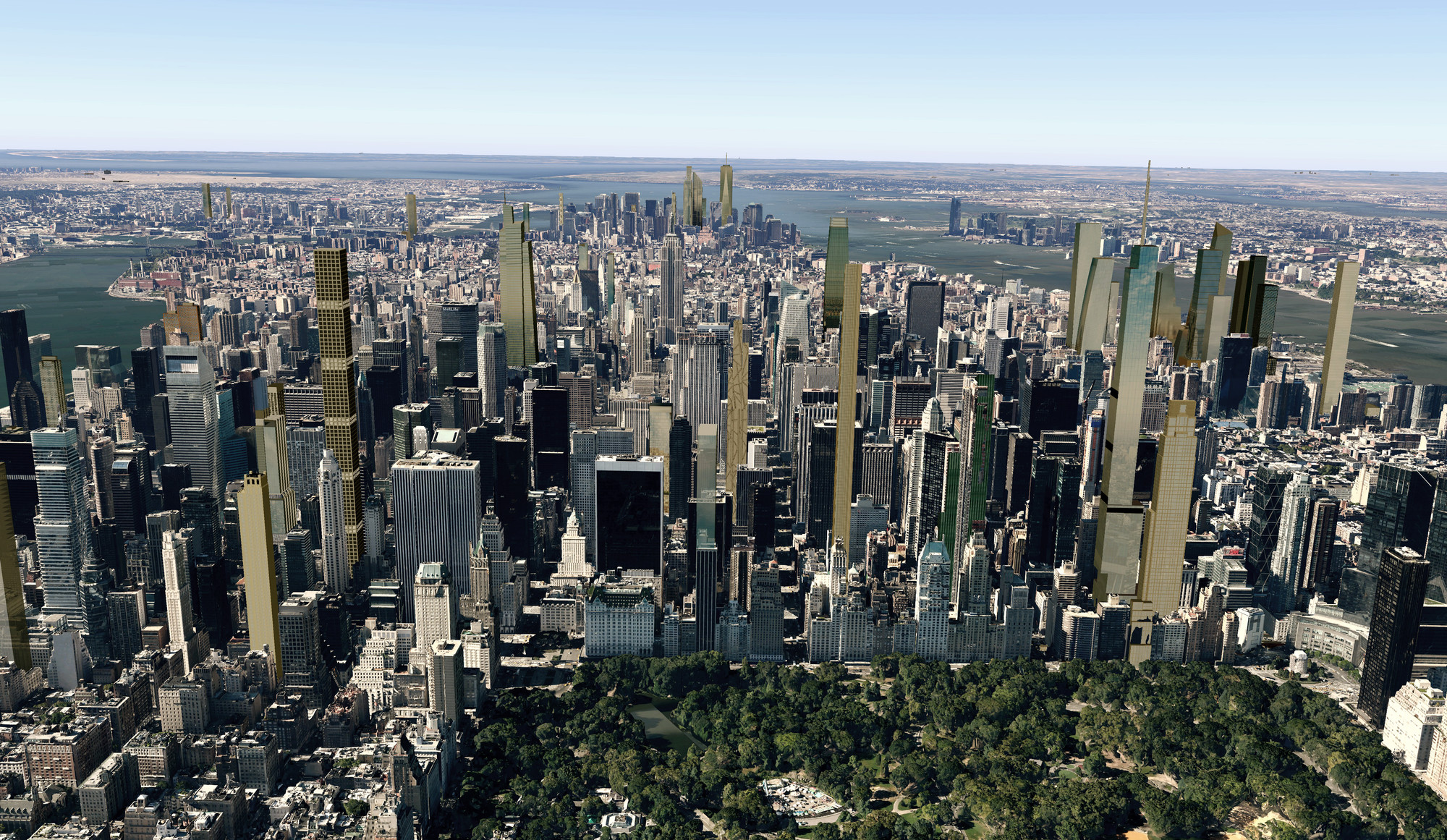

In recent years, it's been difficult to miss the spate of supertall, super-thin towers on the rise in Manhattan. Everyone knows the individual projects: 432 Park Avenue, One57, the Nordstrom Tower, the MoMA Tower. But, when a real estate company released renders of the New York skyline in 2018, it forced New Yorkers to consider for the first time the combined effect of all this new real estate. In this opinion article, originally published by Metropolis Magazine as "On New York's Skyscraper Boom and the Failure of Trickle-Down Urbanism," Joshua K Leon argues that the case for a city of the one percent doesn't stand up under scrutiny.

What would a city owned by the one-percent look like?

New renderings for CityRealty get us part way there, illustrating how Manhattan may appear in 2018. The defining feature will be a bumper crop of especially tall, slender skyscrapers piercing the skyline like postmodern boxes, odd stalagmites, and upside-down syringes. What they share in common is sheer unadulterated scale and a core clientele of uncompromising plutocrats.