"I look for inspiration (or opportunities) from people and places rather than looking for people and places to host my ideas." -- Julia King

Regardless of whether or not Shigeru Ban deserved to be awarded the profession's highest prize this year (there are vociferous opinions on both sides of the issue), there is one thing that is certain: architecture is going through some serious growing pains. And perhaps no one encapsulates architecture's shifting direction better than Julia King, AJ's Emerging Woman Architect of the Year.

Pursuing a PhD-by-practice via the Architecture for Rapid Change and Scarce Resources (ARCSR) in the slums of India, Ms. King realized very quickly that the last thing these communities needed was architecture - or rather, what is traditionally considered "architecture." After all, community-members were already experts in constructing homes and buildings all on their own. Instead, she put her architectural know-how towards designing and implementing what was truly needed: sewage systems. And so - quite by accident, she assured me - the title "Potty-Girl" was born.

In the following interview, conducted via email, I chatted with Ms. King about her fascinating work, the new paradigm it represents for architecture, the need to forego dividing the "urban and rural" (she prefers "connected and disconnected"), the serious limitations of architecture education, and the future of architecture itself. Read more, after the break.

"Speaking from personal experience: none of my formal training or professional practice gave me the skills required to work in such contested spaces. Walking around a slum is a humbling experience. They are very complex and rapidly shifting environments." -- Julia King

AD: Can you describe the work you do for those who may not be as familiar? What projects have you initiated/worked on, and what inspired you to work on them?

JK: In 2010 I got a full scholarship to pursue a PhD-by-practice within the department Architecture for Rapid Change and Scarce Resources (ARCSR) at London Metropolitan University. A fantastic programme run by Maurice Mitchell and the PhD department run by Peter Carl. Doing a PhD by practice meant that my research was embedded in live projects that I have mostly initiated. The research was facilitated by an existing relationship between ARCSR and an Indian NGO, Centre for Urban and Regional Excellence (CURE). It was then that I started doing projects in a slum resettlement colony on the edge of Delhi called Savda Ghevra.

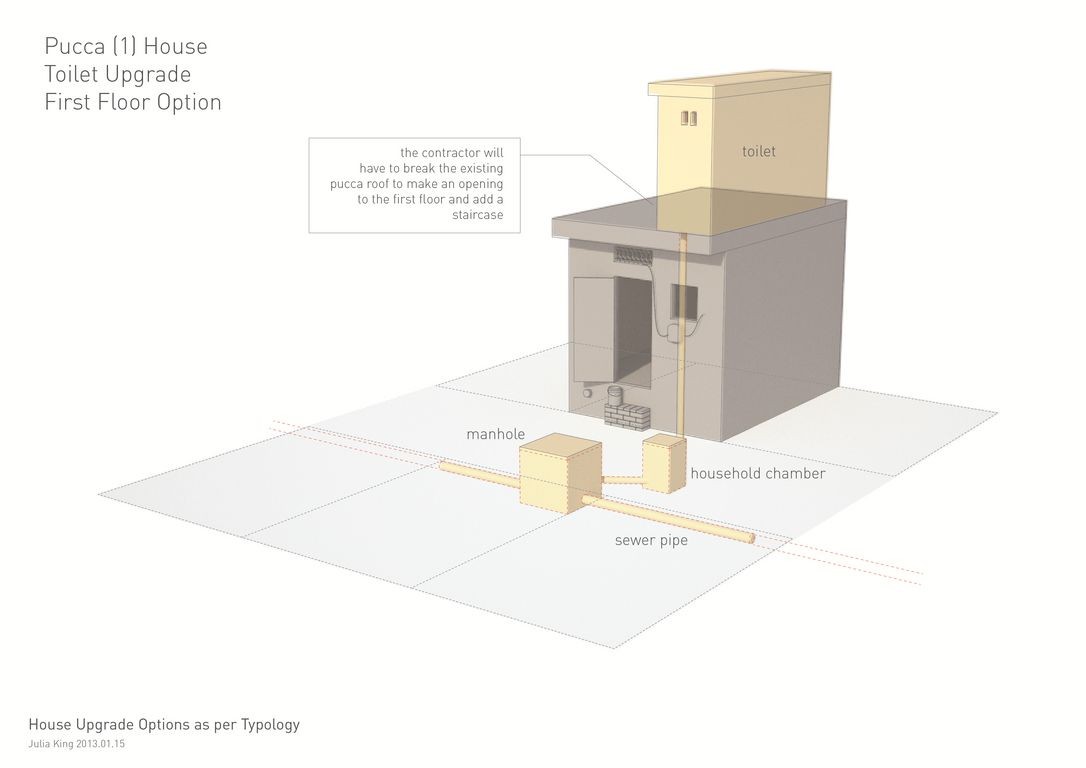

To date I have completed housing and sanitation projects and run various ferrocement workshops – all projects that I initiated and with CURE acting as the implementing agency. The largest project - a decentralized sanitation system - delivers infrastructure enabling 322 households (approximately 2000 people) to have toilets in a community which prior to this mostly defecated in the open.

I have now embedded my architecture and research practice within the same NGO, which has opened lots more projects. Currently I am working on redesigning (and re plumbing) multiple Community Toilet Complexes in Delhi, a slum upgrade plan for two wards in East Delhi (which includes drains, toilets, landscaping, solid waste, and housing) and a project along the Taj East Drain in Agra. Other initiatives are housing upgrades – I plan to launch a kickstarter campaign for a ‘Minimal House’ project soon so watch this space - and I am continuing work in Savda Ghevra, mostly connecting houses to the sewage infrastructure.

I cannot express how important my relationship with CURE is. With the recent publicity surround the Emerging Woman Architect of the Year Award I have felt rather uncomfortable, because I am all too aware that as a foreigner I almost get points just for being here (in a slum in India) when the real hard work (the daily grind) has been done by the people who work at CURE. My hope, because no (wo)man is an island, is that my successes are everyone’s successes.

My inspiration: when I arrived to Savda Ghevra back in 2010 I was young (still am) but terribly naïve. I remember thinking I am going to come and build houses but I very quickly realized that if you want to build houses you have to build sewers first. So my inspiration never so much came from me -- it came from the site.

I could have ended up building a library or a bus stand but what was most needed was sewerage – to do what the community couldn’t do themselves so they could get on with what they do very well, which is making towns-through-houses. So in this sense I never decided to become ‘potty-girl’ - that happened by accident. And now I find that I stumbled into one of the biggest issues facing India today. And now sanitation for me isn’t just about shit, but it is a woman's issues and something I have become really passionate about. So I think my inspiration comes from exposure to people and their hopes/aspirations.

I look for inspiration (or opportunities) from people and places rather than looking for people and places to host my ideas.

AD: You’ve made it your mission to work on projects that provide services for underserved communities. What are the challenges involved in these kinds of projects - are they more financial in nature? Bureaucratic? Practical? All of the above?

JK: I have always been interested in the messy stuff, those bits of the city that we don’t understand. Which in the context of India has taken me to slum spaces and marginalized settlements.

And yes, working in poor often disconnected settlements is tough and all sorts of challenges are involved. To reduce and simplify this, from my experience, there are three main challenges:

1. Money. Funding for projects – always a massive challenge – donors love funding schools, not so much sewers.

2. Willingness. Community participation - this is important not just to do what is right but also for there to be ownership to ensure legacy.

3. Permission. Often from the state, which involves navigating complex bureaucratic barriers which India is very famous for.

AD: When you work on these projects - who is your client? What is the client-architect relationship like?

The client is always the beneficiary of what you are doing in that they are not paying for the service, which requires a certain kind of morality. They do sometimes pay (such as the toilet upgrades we are currently working on) challenging the myth that slum dwellers are passive recipients of aid.

However, mostly the ‘true’ client is the donor who is paying for the project and sometimes the state. As an NGO, CURE is inherently a grass roots organization seeking to empower beneficiaries of projects to be part of the process – as such, success is very much based on those relationships which take time to foster. I very much benefit from and piggy back their work, there's a foundation of community mobilization laid, so that I can be informed by the NGO but also the residents, wherever we are working.

AD: In what areas of the world are you interested in working and why?

My main research interest lies in trying to understand a more concrete description/interpretation of what ‘city’ and ‘urban order’ is. And because, perhaps, the problems in India are so basic and visceral it is no surprise I have ended up working here. And so I am right now, exactly where I want to be working.

In principle I am very much a ‘yes’ person – so if someone were to say to me ‘I have a project in (anywhere in the world) are you interested’ my answer would always be yes. There is nowhere in this planet I am not interested in working. However, meaningful work requires commitment to the place and good connections with local partners and this takes time to foster. I think that only now after three years working in Delhi, and having lived here as a teenager, that I am finally comfortable: I understand my limitations, where I can best contribute, where I have the right set up to be able to work, think, and act. And this is mostly because of my very fruitful relationship with CURE. So looking forward I would love to work in other countries – I have always been very curious about the Middle East – but for this to happen I would need to find organizations from which a relationship can grow organically.

AD: In the next century the world’s population will be overwhelmingly urban - and about a third of the population will be living in slums. Considering how large this population is - and how much need there is for quality design - why do you think so few architects are working in these urban environments?

My most recent thought on this is that the rural – urban divide is a misnomer (much like we have stopped talking about informal and formal). What we are seeing particularly in India and China is mass peri-urbanization characterised by an unplanned shift from agricultural to mixed urban land uses, scattered urban development, misuse of natural resources, environmental degradation, and inadequate provision of infrastructure services.

Furthermore, the distinction between urban and rural misses the crucial point: the distinction between those settlements with access to infrastructure and the benefits of education, healthcare, jobs and housing (that what is needed to fulfill one's capacity) and those without. I am trying to come up with a better phrase, but we need to start talking about ‘connected’ and ‘disconnected’ populations.

As such, with most of the world ‘disconnected’ (rural and urban), there is a serious need for good quality design. I say this often - that India’s peri-urbanization is at the same time its greatest challenge but also its greatest opportunity. If done right this can result in positive development lifting millions out of poverty, and if done wrong these disconnected spaces will be sources of conflict (Egypt's a case in point).

Slums (or barrios) in Latin America are emblematic of spaces of conflict and not spaces of production. The overriding problem, no matter how you see this, is that they are both problems of a bad planning culture. Because when you have a city like Delhi which is adding millions over many decades and will continue to do so, planning is always reactive, which results in an incredible disconnect between what is imagined and the actual physical form.

Why are so few architects working in this area? I think there is a complete disconnect with how architecture is taught, practiced, and the reality of cities and more generally the built environment. The focus on architecture as a form of art is still endemic; however this is changing, albeit slowly. And so I think the profession in general has realized that we are irrelevant – it is hard to fact check this but it sounds right to me - globally architects are involved with only 2% of the built environment.

And if we look specifically at India, most growth is happening in tier 2 and 3 cities - most Indians won’t even know their names. These cities have no central planning, little infrastructure and certainly no architects are involved. This is India’s ‘urban’ time bomb. Put simply, architects need to re-enter (or to put it more softly, better participate in) the discourse on city thinking and city building.

AD: Why do you feel that so many architects within developing nations aren’t interested in the public-interest design challenges within their own nations?

More specifically why so few architects work in slum areas is that, as an architect you might not feel very useful. Speaking from personal experience: none of my formal training or professional practice gave me the skills required to work in such contested spaces. Walking around a slum is a humbling experience. They are very complex and rapidly shifting environments.

The project of inclusive city building is universal. Most cities today are becoming essentially gated communities where the poor are being shifted out – so the discourse I find myself often talking about here: the marginalization and displacement of millions - is as relevant to Delhi as it is to London.

AD: Did you feel that the architecture education you received prepared you to take on the kind of work you are interested in pursuing?

What I learned at architecture school that is still useful is 1. how to work hard (to consistently be able to put in long hours) and 2. how to communicate ideas. That is where we differ from sociologists, anthropologists, social workers and economists who dominate the field of development; we can visually communicate our ideas – and when we talk about participation that is key.

AD: In an interview with Architects Journal you said “It is a very myopic vision of architecture if you just see it through the lens of buildings…it is about the process.” What do you mean by that? How can architects use “process” to affect real change in our cities?

What I mean by the process is that if we look at the production of ‘place’ – whether this is a house or a party wall – I believe the architecture is in the institutional order and location rather than just the process that results in a building – i.e the build up. And so when you talk about that process – and let’s say specifically institution building – this is when we can start designing inclusive environments where people can fulfil their capacities.

AD: Do you feel that public-interest design is becoming more “legitimate” in the eyes of architects? Do you sense a cultural shift happening in architecture?

It definitely is. I remember when I was beginning at architecture school I felt that I had to make a choice between - let’s call it ‘development architecture’ / doing good - and success in the eyes of my peers, but also mainstream media. This is no longer the case and the fact that I won the Emerging Women Architect of 2014 is a testament to that. And so we do see a cultural shift happening in architecture. I think the current issue is how can architects meaningfully intervene and how to avoid the pitfalls of patronage.

AD: I was struck that one of the jury members who selected you as the Emerging Woman Architect of 2014 was Marta Thorne, executive director of the Pritzker Prize, who praised your work for “broadening” what we consider architecture to be …. What do you think your winning of the prize means for architecture? What does it say about the way we are recognizing and defining architecture and architects today?

I think how Marta Thorne put it was brilliant and that made me feel really proud. She went on to say that it is about “supporting promise, promise for social action” and I think this is the best compliment to my work I have ever heard.

Practices like Urban Think Tank, URBZ and architects like Anna Heringer and Teddy Cruz (and I know I am missing lots more) are all donning covers of big magazines and have certainly paved the way. Awards like the Holcim Awards are also helping to drive this very much required cultural shift away from this obsession with architecture as a form of art – which is fine – but we must broaden our understanding of architecture and the kind of cities we want to live in.

The interview was conducted and edited by Vanessa Quirk. Learn more about Julia King's work at her website: http://www.julia-king.com/