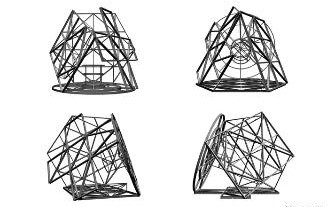

Today marks the fifth anniversary of the opening of OMA’s Prada Transformer. This fantastical temporary structure, erected in 2009 adjacent to Gyeonghui Palace in Seoul, Korea, is one of Rem Koolhaas’ most popular projects to date. Composed of a stark white membrane stretched across four steel frame shapes, The Transformer was often referred to as an "anti-blob" --a hexagon, a rectangle, a cross, and a circle leaning against each other to create a tetrahedron-like object reminiscent of a circus tent. The name Transformer came from the idea that any one of the pavilion's sides could serve as the building's floor, allowing for four unique spaces in one building devoted to exhibitions of modern art, fashion and design.

The Prada Transformer played host to four such events, being lifted up and repositioned onto a different face each time via crane. The first was a garment exhibition, displayed using the hexagonal floor plan. The second, a film festival that took place on the rectangular floor plan. A fashion show was staged using the Transformer's circular floor plan, and an art installation was shown using the cruciform floor plan. As patron Miuccia Prada stated in an interview with The New York Times, “In my mind they [the arts] may be mixed but I want to keep them separate… So the Transformer concept was not for a generic space, but to be very specific, with all things separate in one building.”

We asked OMA's Vincent McIlduff to tell us more about this project. See his answers, a photo gallery and a time-lapse video of the transformation after the break!

ArchDaily: How was the membrane connected to the structure and what exactly is the material?

Vincent McIlduff: The material used, called "Cocoon Membrane" (produced by Cocoon Holland BV) is a synthetic material which is normally used to wrap and protect large pieces of machinery which will remain idle for extended periods of time. The Prada Transformer was the first instance that this Cocoon Membrane was utilized in a purely architectural application. In the case of the Transformer, a fiber mesh was firstly glued directly to the Transformer’s steel structure via an intricate scaffolding system. Then, the membrane was sprayed onto the mesh, becoming taut as it dried. For the large sections of membrane which spanned unsupported between the steel shapes, we first modeled the shapes in 3D, prefabricated them in the Netherlands, shipped them out to Seoul, and then stretched and glued them in place.

AD: Where were the entry points to the Transformer and how did that affect the climate control on the interior?

VM: The service block foyer served as the entry point for public access. As the building rotated, the point at which the corresponding shape would meet this foyer would change. We altered the structure of each shape to allow this zone to be free for entry. The detail for the openings was as temporary in nature as the project itself, a simple slice, a felt hood, and a Velcro seal.

Climate control in the pavilion was provided from the floor. The air was then extracted from above by fans incorporated in the steel structure and in turn exhausted through snorkels seen on the upper exterior of the building.

AD: What was one of the biggest challenges in going from concept to useable building and how was it resolved?

VM: One of the major challenges was in developing a structural system for the connections between the huge steel shapes which were to be assembled on site. The geometry of this tetrahedron was complex, and the specific angles of these connections intricate (however, 5 years on I can still remember each angle!). We then came up with a system to accurately pre-fabricate these points of connection so the large steel shapes could be slotted into their exact position and bolted into place.

AD: What's something cool about the Transformer that wasn't really picked up in the media in 2009?

VM: Definitely the foundations. As each face was turned and placed in its subsequent position the nodes where each shape could be supported moved. We mapped each position for each shape and tried to accumulate them into foundation zones. These zones were then sliced by the ductwork for the pavilion which created strange and inherently beautiful pattern based solely on necessity.

This was not the first collaboration between Koolhaas and Prada, nor has it been the last. OMA has designed numerous catwalks and catalogs for Prada fashion shows, and does so to this day. The firm also continues to be prolific in Asia, in recent years designing the Shenzen Stock Exchange in China, and the Taipei Performing Arts Center in Taiwan. Yet the Prada Transformer endures as one of OMA’s most acclaimed works. Critic Aaron Betsky described it as "event architecture," lauding "its ability to restage, in form and in content, certain aspects of our visual culture." The pavilion's ability to draw attention to the work it displayed, as opposed to itself, was also commended.

The Transformer was dismantled in 2009.

Video via Youtube user Gold Star