Howard Roark, the fictional architect envisioned by Ayn Rand in The Fountainhead, has possibly done more for the profession in the past century than any real architect at all - inspiring hundreds to enter architecture and greatly shaping the public's perception. And, according to Lance Hosey, Chief Sustainability Officer at RTKL, that couldn't be more damaging. In his recent article "The Fountainhead All Over Again," for Metropolis Magazine, he details why it's such a problem, going so far as to accuse Ayn Rand's dictatorial protagonist of committing architectural terrorism.

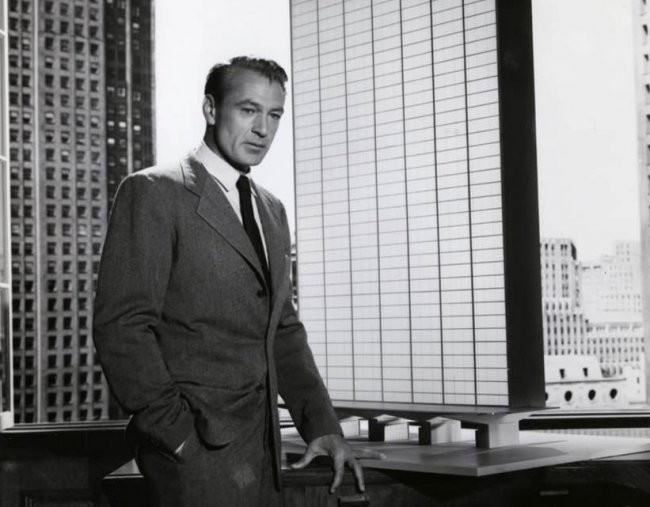

It came out in 1943, exactly 70 years ago this summer. In the movie version a few years later, Gary Cooper played Howard Roark, the character famously modeled after Frank Lloyd Wright. Since then, Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, her “hymn in praise of the individual” (New York Times), has made legions of young people want to become architects. The late Lebbeus Woods wrote that the story “has had an immense impact on the public perception of architects and architecture, and also on architects themselves, for better and for worse.” I’d say worse. In fact, the Fountainhead remains the perfect representation of everything that’s wrong with the profession.

Consider the plot. Here’s the most popular story—maybe the only popular story—ever written about an architect, and in it the hero defends his right to dynamite a building because it wasn’t made the way he wanted. “I destroyed it because I did not choose to let it exist,” declares Roark. At best, this is like a kid throwing a tantrum and smashing his toy blocks. At worst, it’s terrorism masquerading as free speech.

Today, they say the Fountainhead is dead, but everywhere you look architects are portrayed as if they’re strange and special beings, somehow more than mortal. And their views are decidedly Roarkian. Frank Gehry, the most famous architect of our time, has said that denying the architect’s right to self-expression is like denying democracy. But democracy is the will of the majority, not the individual, and Ayn Rand hated democracy because she felt that it crushes personal freedom. When the lines between individualism and democracy blur, it’s safe to say that Rand’s ghost still haunts us.

Yes, the Fountainhead is alive and well among some architects. Call them F*heads.

To celebrate the anniversary of The Fountainhead here’s a look at how it continues to characterize the most celebrated designers.

The F*heads know best—or think they do.

“[The creator] held his truth above all things and against all men.” —Howard Roark

Angel Borrego Cubero’s forthcoming documentary, The Competition, chronicles the development of five starchitects’ designs for one building. At the end of the trailer, Jean Nouvel, in a black hat and cloak, whispers to the director, “I hope you clearly captured the mystery and the deepness.” Delusions of profundity run rampant among the F*heads.

But the architect has no clothes.

Nouvel’s Museé du Quai Branly in Paris has been touted as “green” because of its vegetated façade, but the exotic plants and hydroponics are gluttons for water—green but not sustainable. An earlier project, the Arab Institute, also in Paris, features a kinetic façade that adjusts automatically to changes in light, except that it doesn’t. From the outset, the expensive system had significant problems, including failing gizmos and noisy parts, so for years the façade has been fixed in place. There’s nothing “mysterious” and “deep” about squeaky windows—they’re just annoying.

Last month, after Rafael Viñoly’s “fry-scraper” began reflecting enough heat to cook cars and eggs on the sidewalk in London, New York magazine ran a review of other recent disasters, “When Buildings Attack.” Mishaps are so frequent, the magazine offered a graphic key to distinguish between five kinds of architecturally induced ailments: burning, glare, ice, sway, and death. Evidently, F*heads are dangerous.

The F*heads are martyrs.

“Thousands of years ago, the first man discovered how to make fire. He was probably burned at the stake he had taught his brothers to light.”—Howard Roark whine

After the London incident, Viñoly passed the buck by blaming a “superabundance of consultants” he says he didn’t want: “Architects aren’t architects anymore,” he whined. “You need consultants for everything. In this country there’s a specialist to tell you if something reflects.” He didn’t explain how the same thing happened in Las Vegas a few years ago, when his Vdara hotel was scorching sunbathers.

Martyr complexes are common among the F*heads, who complain about loss of control. In a recent lecture, Rem Koolhaas reportedly lamented about the architect’s waning power, the draining certainty that “things will be as you want them.” And Gehry gripes, “I don't know why people hire architects and then tell them what to do.”

The creator, announces Roark, “needs no other men.” But architects really do “need consultants for everything” because no single person or profession knows everything, and listening to the rest of the team might help avoid, say, unwittingly roasting the neighbors.

The F*heads don’t care about you.

“The creator serves nothing and no one. He lives for himself.” —Howard Roark

Anyone who has ever toured any Frank Lloyd Wright house has heard the same old stories about the roof leaking on the dining table, the owner asking the architect for help, and Wright’s reply: “Move the table.” The price of genius? Wet furniture.

In the past couple of years, after nearly a decade of development, Pritzker-winner Rem Koolhaas finally oversaw completion of the CCTV Tower in Beijing. Its broken-trellis façade streaks terribly from rain and soot, and very little of the interior has been leased, so the owners are commissioning other architects to make the interior more habitable. Last fall, the Huffington Post called CCTV one of “the world’s ugliest skyscrapers,” “a 44-story Mobius strip of awfulness.”

Yet, in 2010, a group of elite architects voted CCTV one of the most important buildings of the past 30 years, and New York Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff hailed it as possibly “the greatest work of architecture built in this century.” Describing the building as “an eloquent architectural statement about China’s headlong race into the future,” Ouroussoff revealed the elitism that characterizes much of architectural theory. Do communities want architects (especially foreign ones) to create “statements” about them, or would they prefer their surroundings to nourish and enrich their lives?

All of this raises an essential question: What is the purpose of design? Is it meant to please the designer, or is it meant to please everyone else—the people who actually live and work in or around buildings? Architectural historian Peter Collins once wrote that behind the original notion of taste—both aesthetic and culinary—was a basic desire to please the consumer, a value that has all but disappeared in contemporary architecture, which tends to develop around the designer’s capricious interests. But, as Collins put it, to focus on personal expression is like judging an omelet by the chef’s passion for breaking eggs; or frying them in the street.

The F*heads seem to believe that the only relevant measure of their work is whether they like it, because the opinions of the rest of us don’t matter.

Move the table.

Lance Hosey is chief sustainability officer with the global design practice RTKL. His latest book is The Shape of Green: Aesthetics, Ecology, and Design (Island Press, 2012).