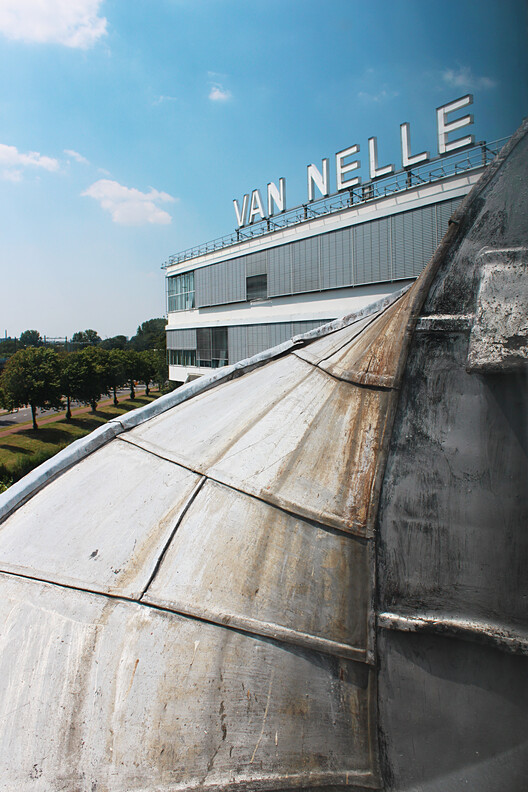

The Van Nelle Factory, located in Rotterdam, is one of the most significant examples of Modernist Industrial Architecture. Designed by Johannes Andreas Brinkman and Leendert van der Vlugt between 1925 and 1931, with the involvement of Mart Stam — a pioneer in modernist furniture design and architecture — the factory was conceived as a progressive and functional building for processing coffee, tea, and tobacco.

Envisioned as a "daylight factory", the Van Nelle complex introduced revolutionary architectural and social concepts for its time. By integrating glass, steel, and concrete into an open, rational layout, it demonstrated how design could transform industrial processes while improving the lives of the people within. It was not merely a space for production but a symbol of optimism, representing the potential of architecture to reshape industries and communities.

Today, the Van Nelle Factory is a testament to modernist architecture's enduring relevance. Its adaptation into a hub for creative industries underscores its timeless design and resilience. Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2014, the factory exemplifies the ideals of the New Objectivity (Nieuwe Zakelijkheid) movement in the Netherlands, which prioritized functionality, rationality, and clarity in architectural design. The factory also marked a turning point in Dutch architecture, demonstrating the potential of modernist principles to transform industrial design. Its success inspired a generation of architects and reinforced Rotterdam's reputation as a hub of architectural innovation.

Modernity in Motion: Light, Space, and Function

Commissioned by the Van Nelle company during a period of rapid industrial and societal transformation in the Netherlands, the factory reflects the ambition of a forward-thinking enterprise. Designed between 1925 and 1931, the project was a response to the evolving demands of modern production. While many industrial buildings of the time relied on heavy masonry and dense layouts, the Van Nelle Factory embraced a radically different approach through the use of reinforced concrete, steel, and glass. This combination allowed for an open and adaptable structural system that became a hallmark of modern architecture.

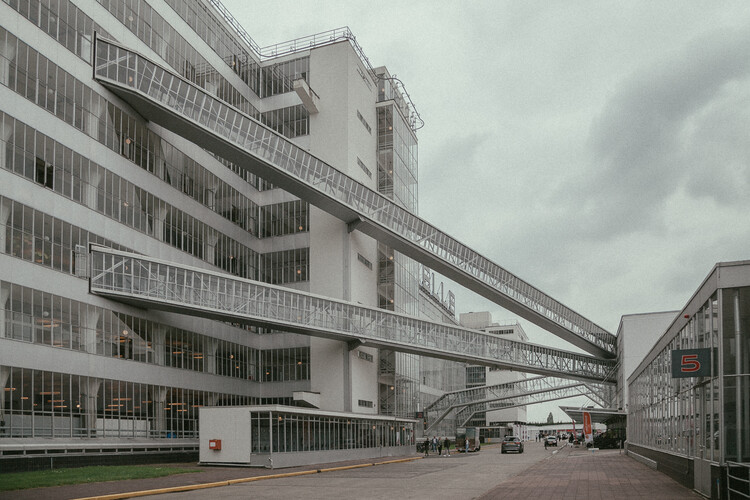

The factory complex is meticulously organized into a series of interconnected buildings, each tailored to a specific stage of production. Wings dedicated to processing coffee, tea, and tobacco are complemented by storage facilities, offices, and loading docks. Elevated conveyor belts and bridges connect these structures, ensuring efficient workflows and minimizing disruptions. This systematic spatial organization reflects not only industrial precision but also an architectural commitment to functionality.

One of the principles that allowed the Factory seamless interplay between design, materials, and purpose — making it a key example of modernism's transformative potential of the industry — was the "daylight factory" concept — a prioritization of the natural light to foster healthier and more efficient working conditions. This progressive vision not only aligned with the ideals of the New Objectivity movement but also set a benchmark for how industrial spaces could be designed to support the people within them — an uncommon consideration in industrial facilities of the early 20th century.

The building's expansive steel-framed glass facades, which filled the interiors with natural light, were instrumental in transforming the factory into a healthier workspace and a sharp departure from the dim and oppressive factories of the previous century. Unlike the cramped, poorly ventilated factories of the 19th century, the Van Nelle Factory featured well-lit, open interiors with high ceilings and ample airflow. This innovative use of materials and layout configuration enhanced productivity and improved the physical and psychological well-being of workers.

The factory also demonstrated a nuanced understanding of the distinct roles played by male and female employees. Women, who were primarily responsible for tasks such as sorting and packaging, worked in spaces that offered optimal natural light and ventilation. These areas were thoughtfully arranged to ensure comfort and efficiency. Men, who handled machinery and loading operations, were allocated spaces designed for functionality and safety. Additionally, the factory provided amenities that were rare for the era, including separate restrooms, designated break areas, and communal spaces for relaxation. This planning, informed by the tasks and needs of its workforce, not only enhanced daily working conditions but also reflected a broader cultural shift towards more humane industrial practices.

Spaces and Functions: An Industrial Revolution in Design

The Van Nelle Factory is a definitive example of the New Objectivity movement, which emerged in Germany and the Netherlands in the 1920s. This movement rejected the ornamental excesses of previous architectural styles in favor of designs rooted in functionality, clarity, and honesty. Aligned with the principles of the Bauhaus and International Style movements, the Van Nelle Factory resonates with the works of architects like Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier. Its minimalist aesthetic, rational planning, and use of modern materials reflect the technological optimism of the era.

The factory's open-plan interiors prioritize flexibility and efficiency. The reinforced concrete skeleton allows for large, uninterrupted spaces, accommodating machinery and workers with minimal structural interference. This adaptability was critical for evolving production processes, enabling the reconfiguration of layouts as needs changed. Spaces are rationally organized into distinct zones for processing, storage, and packaging, streamlining workflows and minimizing unnecessary movement of materials.

The circulation system, a hallmark of the factory's design, is functional and visually striking. Elevated walkways and glass-enclosed bridges connect buildings, ensuring a seamless flow of goods while symbolizing the movement and dynamism of industrial activity. These structures, suspended between buildings, created a sense of interconnectedness and efficiency while also contributing to the overall aesthetic of the complex. Conveyor belts, ramps, and a network of elevators facilitated vertical and horizontal movement, optimizing internal logistics and reducing manual labor.

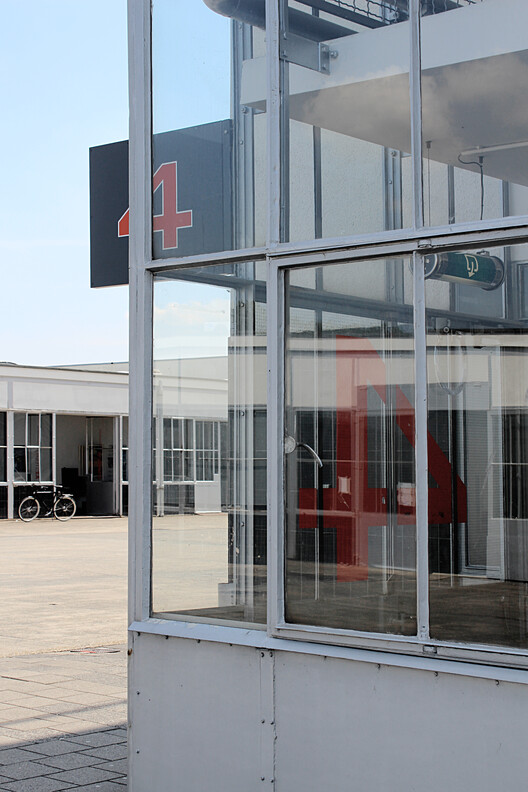

Each building within the complex was meticulously designed to fulfill a specific function. The production wings, for example, were tailored to the unique requirements of processing tobacco, coffee, and tea, incorporating specialized machinery and layouts. The storage facilities were robustly built to secure raw materials and finished goods, while administrative offices were thoughtfully positioned to provide oversight without interrupting operations.

The factory's commitment to its workers is evident in the design of its amenities. Separate facilities for administrative staff and workers underscored the site's functional hierarchy. Workers' spaces included well-ventilated canteens, locker rooms, and rest areas designed to promote comfort and well-being. Meanwhile, green spaces and open-air terraces connected employees to nature, creating a healthier and more enjoyable working environment.

Form Meets Function: The Technical Artistry

The building's reinforced concrete skeleton was central to its groundbreaking construction. Unlike traditional factories that required load-bearing walls, this frame provided the flexibility to create expansive, column-free interiors. This innovation enabled efficient workflows and optimized spatial organization, a design feature rare in industrial buildings of the era. The structural system also supported the use of curtain walls made almost entirely of glass, a feature that distinguished the Van Nelle Factory from contemporaries like Albert Kahn's Ford factories in Detroit, which prioritized functionality over transparency.

Prefabrication played a pivotal role in the construction process, showcasing the efficiency and forward-thinking methodology of the architects and engineers. This approach significantly reduced construction time and costs, a progressive strategy that mirrored the building's purpose of modernizing production. Compared to buildings such as Walter Gropius's Bauhaus in Dessau or Peter Behrens's AEG Turbine Factory, the Van Nelle Factory went a step further by scaling prefabrication to meet the demands of a large industrial complex while maintaining design precision and flexibility.

The site itself posed unique challenges that further illustrate the ingenuity behind its construction. Built on reclaimed polder land, the marshy soil required extensive groundwork to ensure stability for the concrete structure. Advanced foundation techniques, including deep pilings, were employed to distribute the building's weight evenly across the unstable terrain. This attention to engineering detail reflects the intersection of architectural ambition and technical expertise that defined the project.

The foundations were supported on numerous long reinforced concrete piles, which consolidated the stability of the ground. The piles were prefabricated on-site from 1926 onwards, and were inserted by a steam pile-driver. This was a foundation technique pioneered in the Netherlands at the time, and is still today considered to be a remarkable technical achievement. The load-bearing structure for the buildings is in reinforced concrete, using mushroom-shaped vertical columns supporting horizontal girders and a floor. ICOMOS technical evaluation

Preserving Modernism: The Adaptive Reuse of the Van Nelle Factory

The Van Nelle Factory remains a powerful symbol of Modernist ideals and industrial progress. Its innovative use of materials focus on functionality, and emphasis on the well-being of workers have made it a touchstone for architects and historians alike. As a UNESCO World Heritage Site, it reminds us of architecture's transformative potential to shape not only spaces but also the lives of those who inhabit them.

ICOMOS considers that the Van Nellefabriek is technically one of the most accomplished industrial complexes ever built, and one of the great aesthetic successes of Modernism and Functionalism in architecture during the inter-war period. In terms of industrial architecture, it is an eminent example which illustrates the values of the relationship with the environment, particularly with the canals and transport networks, of rational organisation of production and mechanical handling flows, and of maximum use of daylight through the large-scale use of a curtain wall of glass reinforced with iron. It expresses the values of clarity, fluidity and the opening up of industry to the outside world. ICOMOS technical evaluation

Today, the Factory serves as a vibrant hub for creative industries. Following its closure as a production facility in the 1990s, the factory underwent an extensive adaptive reuse process, led by the architecture firm Broekbakema. The redesign carefully preserved the building's original character while introducing new functions, such as offices, studios, and event spaces.

This transformation has maintained the factory's architectural integrity while ensuring its continued relevance in contemporary society. It also demonstrates the flexibility of its modernist design principles, which allowed the building to adapt seamlessly to new purposes. The factory now hosts a variety of events, from business conferences to cultural exhibitions, reinforcing its role as a dynamic space that bridges industrial heritage with creative innovation.

This feature is part of an ArchDaily series titled AD Narratives, where we share the story behind a selected project, diving into its particularities. Every month, we explore new constructions from around the world, highlighting their story and how they came to be. We also talk to the architects, builders, and community, seeking to underline their personal experiences. As always, at ArchDaily, we highly appreciate the input of our readers. If you think we should feature a certain project, please submit your suggestions.