Advancements in 3D printing technology are progressing at an unprecedented pace, accompanied by a parallel surge in computational power for manipulating and creating intricate geometries. This synergy has the potential to offer architects an unprecedented level of artistic freedom in regards to the complex textures they can generate, thanks to the technology's remarkable high resolution and rapid manufacturing capabilities. If the question of production was out of the way, and architects could now sculpt virtually anything into a facade effectively and efficiently, what would they sculpt?

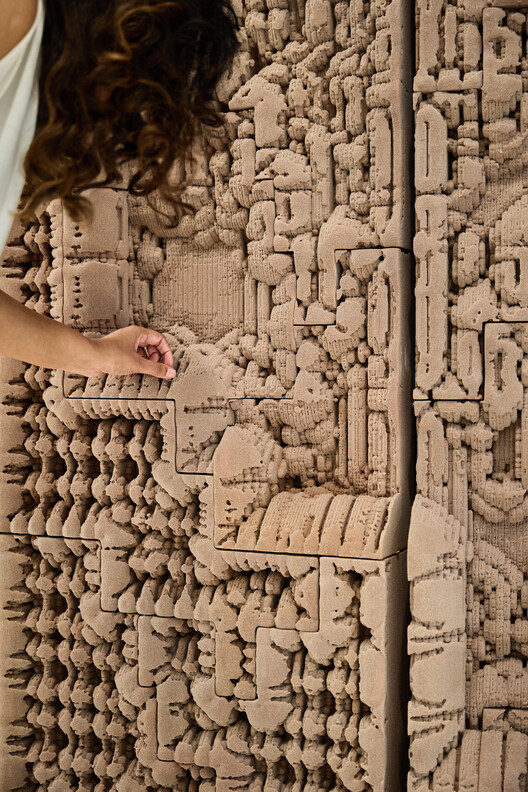

Although we have seen development in the high-resolution 3D printing field in the form of prototypes, in the past year, we have witnessed the materialization of architectural projects using the technology at the facade level. Studio RAP in Amsterdam has effectively manufactured 3D-printed modularized systems that use algorithmically generated geometries. Just last year, they wrapped up "Ceramic House," a boutique store in Amsterdam, constructed by using individually 3D printing ceramic tiles mounted on a laser-cut stainless steel frame, employing algorithmic design inspired by the art of weaving.

So far, much 3D-printing architectural prototyping has been based on manipulating its structural viability and layered manufacturing process, testing materials, and the limits of the high-resolution architecture that can be produced. Plenty of research from ETH Zurich has explored the potential of 3D printing in fabricating richly detailed parts, including developing highly ornamental concrete columns and metal screens. Traditional construction techniques and craftsmanship have also been used as inspiration to create highly textural 3D printed pieces based on traditional craftsmanship techniques.

Related Article

From Decarbonization to Ornamental Expression: Innovative 3D Printed Projects From 2023

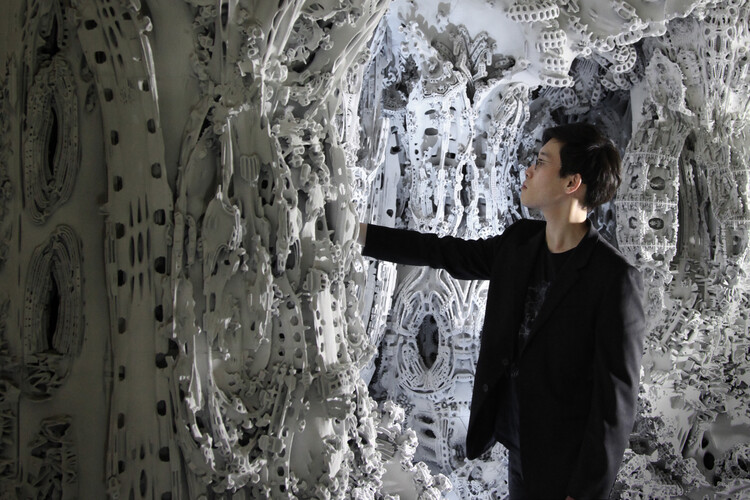

While so much of the testing of the technology has had to do with evaluating its limits, this still leaves open-ended questions about aesthetics. Diving into prototypes that study the artistic opportunities using this technology are some of the works of Michael Hansmeyer and, most recently, Barry Wark. They both work with computer-generated, nature-inspired art. Michael Hansmeyer and Benjamin Dillenburger write algorithms based on processes they observe in nature; these create incredibly complex geometries that they have been able to 3D print, including the "Arabesque Wall" and "Digital Grotesque II." Barry Wark's AI-developed artwork mimics nature's erosion processes, creating forms that blur the lines between the organic and the ornamental.

The incorporation of these technologies into architecture is still in its early stages. As 3D printing and image-generating technology advances, questions about artistry, decoration, and ornamentation in architecture will unavoidably open up. Does this become the space for more architectural and artistic interdisciplinary work? Does it present an opportunity for architects to draw inspiration from art and sculpture? With the imagery production capabilities at our hands, it makes no sense to follow nostalgic notions of ornament. The availability of ultra-fast image-generating software and the manufacturing opportunities that 3D printing brings opens up a new world for architects to explore—creating new possibilities for creativity and innovation, as well as the chance to bring more expressive textures to our architecture and cities.