You can get into Architecture for one of two reasons: good architecture or bad.

For Cameron Sinclair, the co-founder of Architecture for Humanity, it was the latter. As a kid, Sinclair would wander his rough-and-tumble South London neighborhood, contemplating how it could be improved (and creating elaborate Lego models to that effect). Instead of soaring skyscrapers or grand museums, he was inspired by buildings that “integrated your neighborhood in a way that made people feel like life was worth living.”

But that’s not Architecture. Or so he was told when he went to University.

Architecture Schools have created curriculums based on a profession that, by and large, doesn’t exist. They espouse the principles of architectural design, the history and the theory, and prepare its hopeful alumni to create the next Seagram Building or Guggenheim.

Unfortunately, however, the Recession has made perfectly clear that there isn’t much need for Guggenheims – certainly not as many as there are architects. As Scott Timberg described in his Salon piece, “The Architectural Meltdown,” thousands of thousands are leaving the academy only to enter a professional “minefield.”

So what needs to change? Our conception of what Architecture is. We need to accept that Architecture isn’t just designing – but building, creating, doing. We need to train architects who are the agents of their own creative process, who can make their visions come to life, not 50 years down the road, but now. Today.

We’ve been trained to think, to envision and design. The only thing left then, is to do.

More on the public-interest model and the future of Architecture, after the break…

The Powder-keg in the Academy

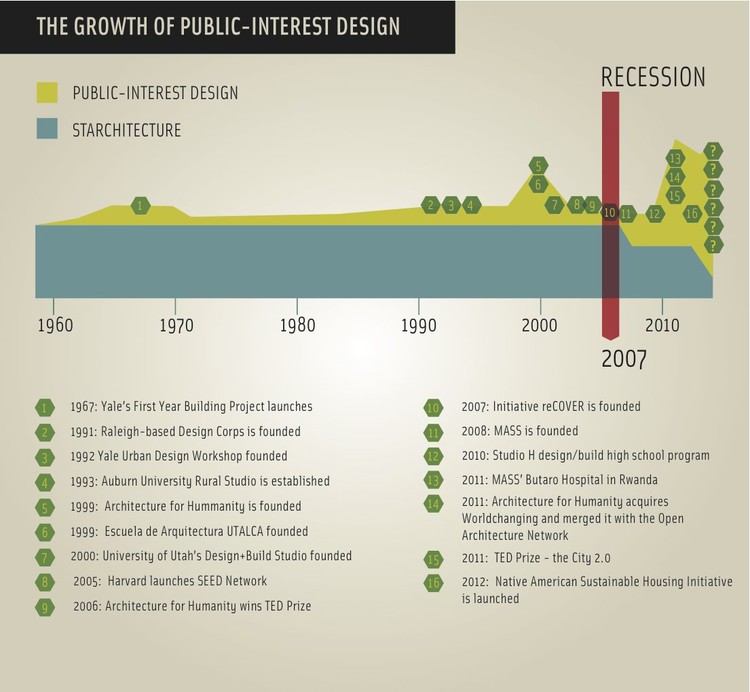

In 1967, Yale University’s Department of Architecture founded an initiative that allowed students to design and build for real-live clients in economically depressed New Haven, forcing them out of the studio, hammers in hand, and into the community.

The effect of the First-year Building Project on Yale students was one of empowerment. As Robert A. M. Stern, the current dean, has noted, the program reintroduced “the reality of architectural experience into the ideality of the Academy,” and made students realize “They didn’t have to be old and hoary to build; they could make things now.”

But, after the revolutionary spirit of the ‘60s passed, the spark somewhat subsided. It wasn’t until the 1990s that it was ready to catch fire. And spread.

1993. Samuel Mockbee and Dennis K. Ruth establish the Rural Studio at Auburn University, where students gain practical experience by building in impoverished rural Alabama. The University of Utah soon follows suit with its Design+Build Studio. 1999. The University of Talca, located in an under-developed corner of Chile, creates an entire curriculum based on the design-build approach, where students must design, finance, and build if they are to graduate.

The Design Corps (1991) and Architecture for Humanity (1999), which both harness the brain/muscle power of Architects to improve the built environment in struggling communities, spring up and gain recognition.

2005. A group of experts meet at the Harvard School of Design to discuss the “global movement” of community-based design, resulting in the creation of the SEED (Social Economic Environmental Design) Network of design professionals and local citizens “engaged in a public-health version of architectural practice.”

And then, an extraordinary thing happens. 2007, the Great Recession hits the U.S.

Architecture for the 99%

Unemployment and underemployment have soared across the country, architecture firms have shrunk, and jobs are ever more scarce, but Architecture continues to rely on its post-war model, what Guy Horton describes in “The Architecture Meltdown” as: “idealism, dues paying, hierarchy, optimism and a heroic self-image financial realities.”

Young graduates and professionals continue to be particularly pommeled by the economy, becoming a “lost generation.” As The New York Times recently put it: “Want a Job? Go to College, and Don’t Major in Architecture.”

However, slowly, surely, architects are putting cracks in the model that has let down so many of their peers.

As Thomas Fisher, of the University of Minnesota, has pointed out in his “Architecture for the Other 99%,” public-interest design firms have an edge that traditional firms don’t: they provide for the “needs of the billions of people on the planet living in unsafe and unhealthy conditions.” That’s billions of untapped clients.

For example, the Non-Profit Firm MASS (Model of Architecture Serving Society) Design Group, founded in 2008 by Michael Murphy and five classmates of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, sees its clients as traditionally ”underserved communities.” Their first major project, the Butaro Hospital in Rwanda, completed in 2011, garnered such press that they are now receiving paying commissions.

Spot-lighting MASS and the rise of public-interest design in their March Issue, The Architectural Record, while certainly recognizing the movement, betrayed a healthy dose of skepticism for this new model. Titles read: “Can public-interest design become a viable alternative to traditional practice?” and “Does ‘Doing Good’ Pay the Bills?”

One could (cheekily) respond: Does ‘Doing Architecture’ pay the bills?

But, cheekiness aside, if public-interest design is to offer an alternative model, The Record should indeed be exploring its viability, which critically depends on a healthy knowledge of business development as well as a global outlook.

Murphy, of MASS, “spends half his time on business development, not design,” and must constantly seek funding; however, he employs 21 people full-time with outposts in Rwanda, Haiti, Boston, and Los Angeles. Sinclair, of Architecture for Humanity, has seen his small operation grow into a a million-dollar business: a network of over 50,000 architects working with thousands of clients in 25 countries across the globe. And he’s hiring.

With the market as grim as it its, schools should be preparing students to take advantage of these emerging markets. As Jenn Kennedy, author of Success by Design, has noted, the Recession “is an invitation for architecture schools to consider how to better prepare their students with business tools and real world experience.”

Design-build curriculums (which encourage real world experience) are perfectly suited to this end, giving students the professional skills of client relations, strategic thinking, and business development they’ll need to survive in today’s economy.

There’s a reason why non-architects are so much more enamored with the profession of architecture than many architects are. For the layman, the architect is half idealist-half realist, an intellectual that pulls his creations from the ether down to the ground with steel, glass, and wood. He thinks, yes, but more importantly, he creates.

Now, to reality. Most architects, in the process of becoming architects, have become disillusioned and cranky. If they have a job (nowhere near a given in this economy), they’re worker drones, and they’re tired: of being over-used and under-paid, of being un-acknowledged for their efforts and beaten up for their mistakes. To be frank, they’re working like dogs, but not creating much at all.

But let’s go back to 1967 for a minute. To those empowered Yale Students who realized that Architecture wasn’t an abstract project that would happen to them fifty years down the line, but a physical possibility for the here and now. Who were entering a profession where their technical expertise could, if they so chose, provide a service to hundreds of communities, hundreds of potential clients, and build a life’s work to be proud of.

If the recession has taught us anything, it’s that the current model need not, and cannot, go on. Community-based/Public-interest design (in firms and curriculums) offers not just a means of bettering life in needy communities, but a new model to follow, one that cultivates physical relationships with the projects we envision and the clients we serve, and gives us the opportunity to create what we have been trained to design.

In the spirit of Architecture week and the on-going “I Love Architecture” Campaign, it’s time to remember what makes Architecture great, and fall in love with it again. We must bring building back on par with designing, and recognize our profession’s tremendous power: to make life more worth living.

References

Fisher, Thomas. “Architecture for the 99%” MetropolisMag.Com. February 8, 2012. .

Hayes, Richard W. “Activism in Appalachia: Yale architecture students in Kentucky, 1966-69.” Agency: Working With Uncertain Architectures. Eds. Florian Kossak and Tatjana Schneider. 29-30. Accessed via Google Books.

Hill, David. “The New Frontier in Education.” Architectural Record. March 1, 2012.

Hughes, C.J. “Does ‘Doing Good’ Pay the Bills?” Architectural Record. March 2012. .

McGuigan, Cathleen. “Can public-interest design become a viable alternative to traditional practice?” Architectural Record. March 2012. .

Timberg, Scott. “The Architecture Meltdown.” Salon.com. February 4, 2012. .